In 1893 Josiah Conder wrote the first book by a European about Japanese gardens, which has been the single greatest influence on Japanese garden design in the West. Yet given that Japanese plants and gardens in the Japanese style are now well known in Britain it’s strange to think that up until 40 years before Conder’s book Japan and its gardens were largely unknown to the western world.

It was only in 1854 that Japan was forced to open up to western trade and influence by the threat of war from the Americans. Within a decade Japan and all things Japanese had become one of the dominant themes in all of western culture influencing everything from art and fashion to interior design and gardens.

This is the first post in a series about the links between Japan and British and other European gardens. I’m beginning with the earliest 300 years of western links to “Giapan” when it was first described as “the noble islande otherwise knowne as Japon or Japan”and “the extreme part of the knowen worlde”.

Our early knowledge of Japan and its plants and gardens came as a by-product of commercial expeditions and religious missions rather than any process of simple exploration or planthunting. Having discovered the sea route to Asia via the Cape of Good Hope the Portuguese soon established trading posts around the coast of India, Sri Lanka and Malacca before reaching Canton in 1517. In 1543 one of their ships was caught in a typhoon, and ended up being shipwrecked off the south-west tip of Japan. Amazingly this disaster eventually enabled the Portuguese to establish trade links and it also led in 1549 to the arrival in Japan of a group of Jesuit missionaries led by St Francis Xavier.

detail showing the Portuguese

In a mirror image of what was to happen in late 19thc Europe the arrival of these exotic foreigners – the nanban-jin, or ‘southern barbarians’ as they were known caused enormous cultural and political upheaval in Japan. There are some wonderful Japanese representations of Europeans at this time.

For more on that see “Japan’s encounter with Europe, 1573 – 1853” on the V&A website. and “Japan, Portugal and the World” on the website of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York

Cherry, Plum and Willow, Unidentified artist, early 17th century

Metropolitan Museum NYC

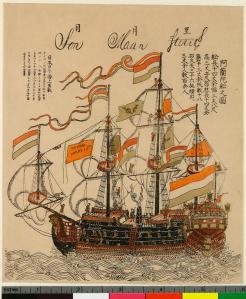

However Portuguese control of trade with Japan did not last long and by the end of the 16th century they were being increasingly challenged. First by the Spanish and then more effectively by Dutch merchants who with the setting up of the Dutch East India Company [Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie or VOC for short] gradually eclipsed them. They began by taking over Portuguese trading posts and then in 1600 the first Dutch ship reached Japan. By a quirk of fate amongst the crew was an Englishman named William Adams. More about him shortly!

Up to this point England had been rather behind in the game. Information gleaned by London’s merchants from their wide European connections was always second-hand and largely based on letters sent back by the Jesuit missionaries to fellow members of the order in Europe. Somehow Richard Willes or Wylles [himself a former Jesuit novice turned Protestant] obtained a few of these letters written by a Portuguese brother with its information about “the Japonish nation”. In 1577 He used them as the basis for a section about the Ilande Giapan, and other litle Iſles in the Eaſt Ocean. in his book The History of trauayle in the VVest and East Indies : and other countreys which was designed as an encouragement to those seeking the fabled North West Passage, round the north coast of Russia to reach the fabled riches of the Orient.

Describing the Japanese as ‘‘tractable, civill, wittie, courteous [and] without deceit’, he gave a lengthy account of things like weather, diet and habits, and raised interest in possible and profitable trade. There was, however, no mention of plants, gardens or even much about the landscape, although even then there was a strong sense of isolation: “The inhabitants of Giapan, never had greatly to doe with other nations.”

Describing the Japanese as ‘‘tractable, civill, wittie, courteous [and] without deceit’, he gave a lengthy account of things like weather, diet and habits, and raised interest in possible and profitable trade. There was, however, no mention of plants, gardens or even much about the landscape, although even then there was a strong sense of isolation: “The inhabitants of Giapan, never had greatly to doe with other nations.”

Some of these letters were probably written by Luis Frois, one of those Portuguese Jesuits who visited Japan and who was to write the earliest systematic comparison of Western and Japanese cultures, in over 600 brief couplets. The original text of this was only re-discovered in the Royal Academy of History in Madrid after the Second World War, and it wasn’t until 2014 that an English language version was finally published, as The First European Description of Japan, 1585. It gives our first insights about Japanese gardens, albeit slight.

Panel from a screen showing a group of young nobles enjoying a game of ball beneath a canopy of cherry trees in full bloom. early 17thc

© The Trustees of the British Museum

What surprised the Jesuits, was that while “we purposefully plant trees in our gardens that will bear fruit; the Japanese place greater esteem on planting trees in their gardens that bear only flowers.” Indeed while “among us, all fruits are eaten when they are ripe, except for cucumbers, which are eaten green; the Japanese eat all their fruit when it is green, except for cucumbers, which are eaten very yellow and ripe” and while “we harvest unripe grapes for flavouring our food; the Japanese harvest them to be pickled with salt.”

One might have also thought the preference for flowers over fruit would have meant a great value being placed on their scent but that was not the case. “Among us, when one picks a fragrant rose or carnation, we first smell it and then examine it visually; the Japanese pay no attention to the smell and take pleasure only in the visual experience.”

Four sliding-door panels showing The Old Plum byKano The style of growing trees was also very different: ‘We work to get our trees to grow straight upward; in Japan, they purposefully hang stones from the branches so that they will grow crooked.” , 1646

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Armour presented to King James I by Tokugawa Hidetada in 1610. Royal Armouries

If you’ve heard of William Adams the first Englishman to reach Japan it’s probably because you’ve read Shogun a novel about him by James Clavell published in 1975, and then turned into 2 tv series, a musical and several games. Adams ended up staying in Japan for the rest of his life, becoming a samurai warrior and a key advisor to the shōgun. However, he didn’t forget his homeland and eventually, in 1613, following an invitation from Adams, John Saris an English merchant arrived in Japan in the hope of setting up a trading station.

Helped by Adams his mission was successful and the shogun sent a present of armour to James I, now in the Tower, and allowed the English to establish a small base on Hirado Island near Nagasaki, which was the main Japanese port trading with Korea and China, and where earlier bases had been set up by the Portuguese, Spanish and Dutch. Over the next 10 years 3 English ships made the return voyage to Japan. Unfortunately the link didn’t last because there were fierce disputes between the western maritime nations over control of trade not just with Japan but the East Indies and China as well. This led to the Amboyna massacre and the East India Company shutting down its base in Japan.

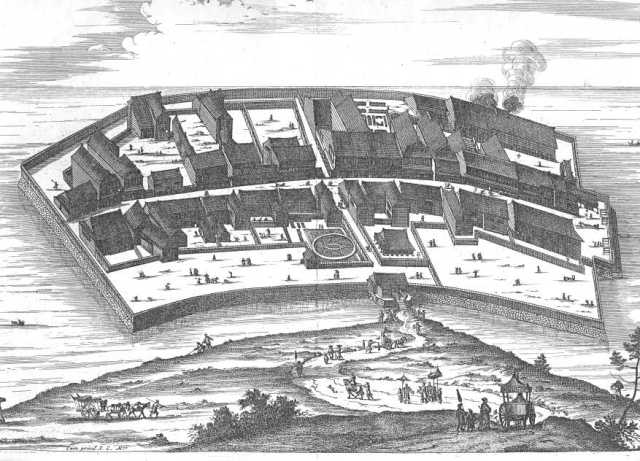

Only a few years later in 1639 the Japanese then shut down almost all external connections and decided to retreat into almost total isolation – in what is now known as the ‘closed country’ (sakoku) period. Europeans, with sole exception of the Dutch, (known as “Kōmō” or “Red Hair”) were no longer allowed into the country and even they were confined to the tiny artificial island of Deshima in the bay of Nagasaki – which was 214 metres long and 64 metres wide. In principle, the inhabitants, who never exceeded 20 in number, were not allowed outside the gate, and the local Japanese, with the exception of those who rendered services such as cooking, interpreting, and prostitution, were prohibited from entering the compound.

As a result direct British interest in Japan seems to have faded somewhat, but for the rest of the 17thc there was still a slow trickle of Japanese objects such as furniture, Porcelain, lacquer and paper screens into Britain. These came via The Dutch East India Company which effectively now had a monopoly of Japanese goods reaching the West. A book published in 1688 showed how to imitate some of the designs through “japanning and varnishing”, a process we would now call lacquering. The designs in A treatise of japaning [sic] and varnishing : being a compleat discovery of those arts were taken from some of these Japanese export pieces, which for the first time showed landscape and plants although obviously not very accurately.

detail from Regni Japoniae nova mappa geographica which ostensibly shows Kaempfer [on the left] drawing a map, although he was long dead when the map was published. It also shows the confused nature of western ideas about Asia and its civilisations.

Japan remained in self-imposed isolation for just over 200 years until 1854, but that doesn’t mean that no information got out. The Dutch at Deshima proved adept at gathering knowledge although they had more difficulty in getting objects such as plants out of Japan. The extent of their success can be seen in the work of Englebert Kaempfer, a German physician who worked for the Dutch East India Company. This and the letters and reports back to Europe evoked romantic images of a secluded country with mysterious customs, that coloured western notions of Japan during sakoku.

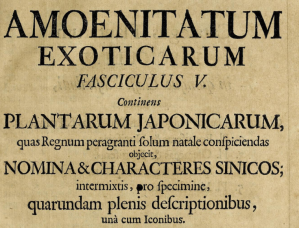

Tsubaki or Camellia japonica from Kaempfer’s Amoenitatum exoticarum

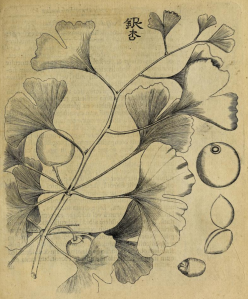

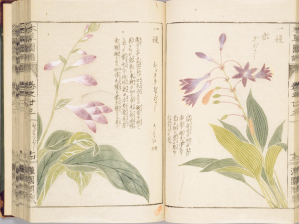

Kaempfer worked at Deshima Island between 1690 and 1692. During that time he was able to gather extensive notes on the history, culture and natural history of Japan primarily during his two excursions accompanying the annual Dutch procession to the capital, Edo – the only time they were allowed off the island. These gave him the opportunity to conduct extensive studies on local plants, and these were later published in 1712 in his “Flora Japonica” (part of a larger work Amoenitatum Exoticarum). Written in Latin it includes illustrations of 23 plants indigenous to Japan – with hundreds of other descriptions in text only, with their names in both Westernised Japanese and Japanese characters [although as you can see Kaemper describes that as “Sinicos” or Chinese.]

Kaempfer worked at Deshima Island between 1690 and 1692. During that time he was able to gather extensive notes on the history, culture and natural history of Japan primarily during his two excursions accompanying the annual Dutch procession to the capital, Edo – the only time they were allowed off the island. These gave him the opportunity to conduct extensive studies on local plants, and these were later published in 1712 in his “Flora Japonica” (part of a larger work Amoenitatum Exoticarum). Written in Latin it includes illustrations of 23 plants indigenous to Japan – with hundreds of other descriptions in text only, with their names in both Westernised Japanese and Japanese characters [although as you can see Kaemper describes that as “Sinicos” or Chinese.]

Kaempfer was also the first westerner to describe Ginkgo biloba which he saw when he was allowed to visit Buddhist monks in Nagasaki in February 1691. He obtained some seeds which he took back to Holland at the end of his tour in 1695 and they were planted in Utrecht’s botanical garden.

[For more on the introduction of Gingko a good place to start is the on-line book by former Director of Kew, Peter Crane, Gingko: The Tree That Time Forgot, 2013]

Unfortunately Kaempfer died before he was able to publish his planned history of the country itself but his manuscript notes survived and were purchased by the botanist and “magpie” collector Sir Hans Sloane who had them translated into English and then published in 2 volumes in 1728.

It was the most comprehensive European account of Japan for over a century and the first in English. It had wide-ranging influence and was soon translated into French, remaining an important account of Japan and Japanese life until well into the nineteenth century.

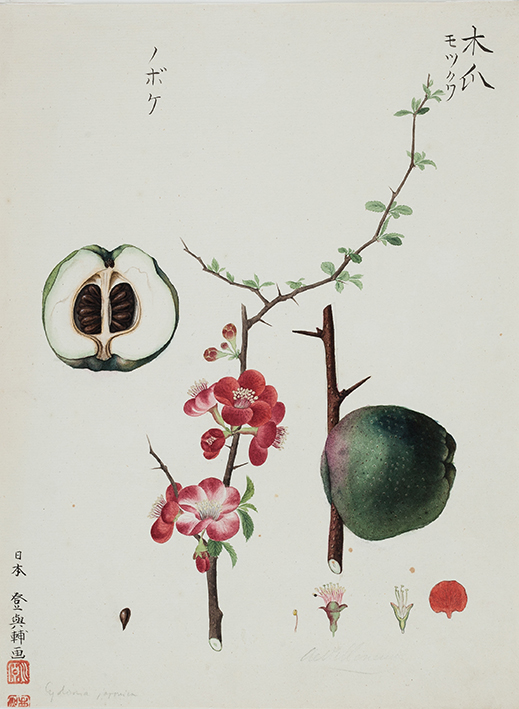

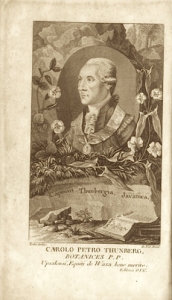

Another significant contribution to western knowledge of Japan and its plants and gardens were made by Carl Pehr Thunberg, a Swede working as a doctor with the Dutch East India Company. He travelled to Japan via several other Dutch bases, notably Cape Town, where he went plant hunting [see this earlier post for more information]. Soon after his arrival in 1775 he gained a reputation helping local medics deal with the “Dutch disease”, better known as syphilis. As a result he was, unlike the other Dutch residents on Deshima, actually allowed to visit Nagasaki itself giving him the opportunity to collect specimens. During his 18 months or so in Japan he collected more than 1000 plants which he described later in his Flora japonica. This formed the basis of the taxonomy of Japanese botany, and was published in 1784 long after his return to Europe. Amongst them were the first European scientific accounts of Paulownia, Hydrangea macrophylla, Kerria and the plants most gardeners know as just Japonica [ Chaenomeles japonica].

To see some of Thunberg’s Japanese plants painted by Japanese artists see Flora Japonica published by Kew as the catalogue for the 2016 exhibition in the Shirley Sherwood Gallery. For more on Thunberg’s importance more widely see Bertil Nordenstam’s article “Carl Peter Thunberg and Japanese Natural History.

However the most significant figure in the pre-open borders time was Philip von Siebold, a German doctor who arrived at Deshima in 1823. He was to remain in Japan for seven years during which time he started a medical school and married a local woman. Their daughter Kusumoto Ine became the first Japanese woman known to be trained as a physician and rose to be the personal doctor to the Empress in 1882.

Siebold made a study of Japanese garden design and the local flora, sending back thousands of herbarium specimens to Europe. More significantly at the end of his stint in Japan he managed to take out actual plants. These included tea plants which he left at the botanical garden Buitenzorg in Batavia and founded the Javanese tea industry. Siebold also introduced hostas to Europe and, slightly less fortunately Japanese knotweed. (See an earlier post or more on that!]

When Siebold returned he lived outside Leiden in a house he named Nippon where he opened a nursery specialising in Japanese plants, and continued to mastermind the shipment of Japanese plants to Europe, despite the difficulties with the sea journey.

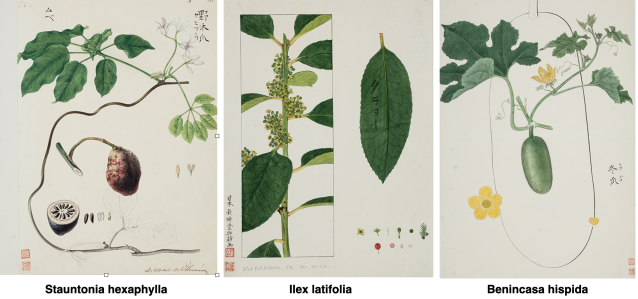

Over 30,000 specimens, together with drawings done for Siebold by Japanese artists, went on view at the Japanese herbarium in Leiden soon after his return. Then, in 1835, together with his colleague Joseph Zuccarini Siebold began to compile his Flora Japonica although it was not finally finished until 1870, four years after his death.

Von Siebold’s contribution to the introduction of Japanese plants to Europe cannot be over emphasised, coming as it did a decade or so before Japan was forced to open ports. Perhaps, then it’s not so surprising then that by the time Queen Victoria came to the throne Japan and its plants were already having an impact on British gardens.

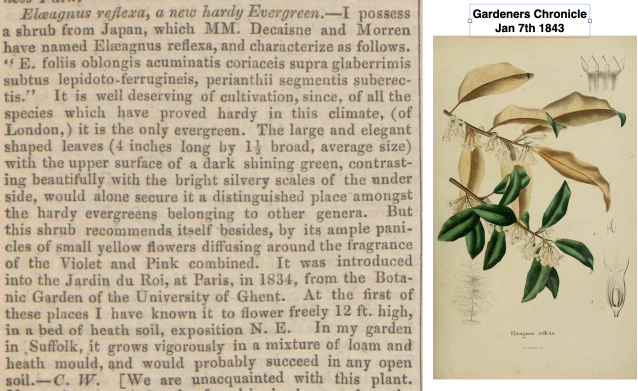

A search of the early years of Gardeners Chronicle showed a couple of references to Siebold himself, or his book or herbarium but quite a few others about Japanese plants such as spirea, “noble Japan lilies”, the Paulownia, or “a new hardy oak”. But Loudon is clear as with “Rhododendron macranthum and R reticulum from japan” that “We know nothing of the two latter.” This sense of newness and simple lack of knowledge of Japan and its plants is summed up by Loudon’s comment in response to a letter in the magazine about “Eleagnus reflex, a new hardy evergreen” from Japan.

He writes: “We are unacquainted with this plant. No such name is to be found in books, nor does the plant occur in that part of Siebold and Zuccarini which has reached us. The leaves resemble those of E. conferta” and he ends with the plea which will be understood by all gardeners…”Can you let us have a plant?”

More on our links with Japan next week

You must be logged in to post a comment.