Did you know that the British Government spent the twenty years between the First and Second World Wars investigating the possibilities of electrifying plants? And did so in almost complete secrecy. It means that last week’s perpetually electrified garden wasn’t quite the complete dead-end I originally imagined and maybe not quite as hare-brained either. In fact it was just the first sign of a complete new science or, as many others would have it, pseudo-science – Electroculture.

Although Benjamin Martin’s perpetual electrification machine that I wrote about last week disappeared without trace it clearly didn’t not stop research and publication about the effects of electricity on plants continuing on both sides of the Channel…and less than a hundred years later The farmer’s guide to Scientific and Practical Agriculture announced that “Electricity maybe classed among special manures” and that was only just the start…![]()

In France, for example, in the late 1770s, the wonderfully named Bernard-Germain-Étienne de La Ville-sur-Illon, Comte de Lacépède, began some experiments watering plants with water which as he put it had been “impregnated with electrical fluid”. He published a 700+ pages long Essay on Electricity in 1781 which reported his findings that the germination of seeds and the sprouting of bulbs was quicker and when plants were electrified, they grew with more vigour than usual.

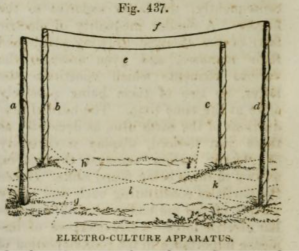

There were other French would-be electricians too, notably the Abbé Pierre Berthelon who had already written about the benefits of electricity and health, and other related subjects. Now he too tried watering plants with “electrified water” delivered from an insulated barrel on a trolley that could be trundled along by the gardener between the rows. In 1783 he published De l’électricité des vegetaux, which included a description of the first electro-culture tool: the electro-vegetatometer!

Franklin’s lightning experiment probably never happened quite like this but it’s a good story nonetheless

You’ll remember the story of Benjamin Franklin flying a kite to attract lightning well that’s what Berthelon aimed to replicate.

He set up miniature lightning conductors to collect electricity from the atmosphere and then distributed the charge via wires across the garden. Don’t ask how precisely – it was too complicated to read and translate 18thc technical French – but the image below should give you the general idea.

But things really start to buzz again in the 1840s when a whole new generation of experimenters, began to test out new theories and report their findings in serious journals. This was probably due to the invention of what was called an “Earth battery” by Alexander Bain in 1841. Bain’s device operated on the same principles as a modern battery except the zinc and copper plates were put into the soil and connected above ground by wires. Plants grown in the area between the two plates grew faster and yielded more. [Follow this link for more info in simple language on earth batteries, how they work and how powerful they can be]

In 1844 Robert Forster, a Scottish landowner, of Findrassie near Elgin used what he termed “atmospheric electricity” to substantially boost his barley crop. The details were reported in The British Cultivator in March 1845, local newspapers across the country and Letters on Agricultural Improvement by John Joseph Mechi who added that Forster was still “indefatigably employed in collecting Electro-Cultural facts from our most eminent electricians “.

I wondered where Forster got the idea from, and discovered that he was far from unique and that there were plenty of amateur scientists who had never stopped trying to perfect a way of getting electricity to boost plant growth. Forster had, for example, read in George Glenny’s Gardeners ‘ Gazette about “an experiment made by a lady” who “caused a constant flow or supply of electricity ( to be afforded by a common electrical machine ) to proceed from a summeror garden-house , and which was diffused by wire to a fixed portion of the surrounding ground; and the effect was,that vegetation did not cease in the winter on the spot under the influence of this wonderful power .” So Forster tried a similar thing with positive results. [South Eastern Gazette, 28th January 1845]

from The Farmer’s Guide

Much of the early history of electroculture in both both Britain and the continent, including Forster’s work, was written up by Edward Solly, a Fellow of the Royal Society, and “Experimental Chemist” to the Horticultural Society who published “On the Influence of Electricity on Vegetation” in the Journal of the Horticultural Society in 1845. Yet scepticism continued with the Farmer’s Guide to Scientific and Practical Agriculture. saying in 1851 that although electricity could be classed as a special manure “No one has as yet been able to reap similar advantages from similar experiments as Dr Forster obtained from his; and it is doubtful..that electro-culture will be prosecuted further for a time.” So, after this flurry, once again I thought that was the end of the strange idea again but again I was wrong.

Lemstrom

In the 1880s Professor Karl Selim Lemström of Helsinki University a geophysicist studying the Aurora Borealis – or Northern Lights – began to wonder if they had an effect on plant growth because he noticed that the trees in the far north grew rapidly despite the short growing season. This led him to start experimenting with the effects of atmospheric electricity on germination and plant growth. Lemström’s results attracted international attention and he was able to conduct some of his later experiments in collaboration with other scientists in Sweden, Germany and at Durham College of Science.

from Electricity in agriculture and horticulture by Lemstrom, 1904

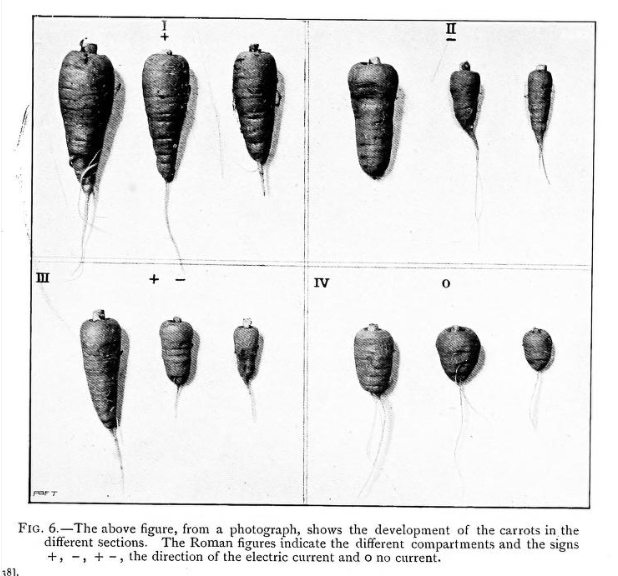

Eventually in 1904 he published Electricity in Agriculture and Horticulture in which he offered his detailed findings that there was “an increase of the harvest of every kind of plant which has come under treatment, but also a favourable change of their chemical compounds” which made fruit sweeter and scent stronger etc.

Paulin’s geomagnetifere

from Le Genie Civil, 1892

Paulin’s geomagnetifere

from Le Genie Civil, 1892

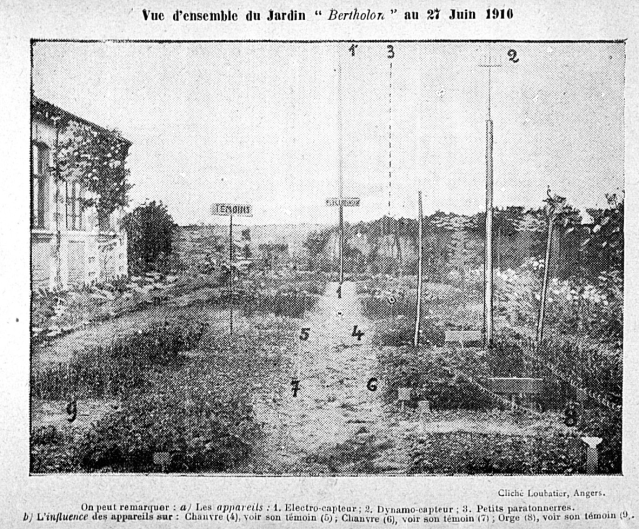

Around the same time in France the Agricultural Institute at Beauvais under its director Father Paulin began what they hoped were a series of experiments to decide once and for all when this electrical charging worked.

Paulin refined Abbe Berthelon’s electro-vegetatometer devising an atmospheric antenna that he called a geomagnetifere. Installed initially in a field of potatoes, plants within its reach were greener, healthier and produced more potatoes. Later it was tried in vineyards and produced sweeter larger grapes that produced better quality wine.

Another researcher, Fernand Basty, installed one in a school garden which he named the after Abbe Berthelon.

Basty then went on to organise the first [and I suspect only] International Conference on Electroculture held at Rheims in northern France in 1912 which showed that there was active research going on across the globe.

Britain had particular reasons to be interested because of food shortages during the First World War caused by a blockade by the German navy. It became a government priority to improve agricultural and horticultural production so in 1918 a group of British scientists set up experiments to test the efficacy of electricity at boosting yields. These generally appeared to show impressive although not universal increases. Nevertheless it resulted in considerable interest from the agricultural and horticultural communities who lobbied the government for further research. In response the Board of Agriculture set up the Electro-Culture Committee to investigate further. Membership was impressive: an interdisciplinary mix of physicists, biologists, electrical engineers, and agriculturalists, including a Nobel Prize winner and six fellows of the Royal Society. It was chaired by Sir John Snell, Chairman of the Electricity Commission.

Unfortunately their field trials, based on the idea proposed by Lemstrom, on a wide range of crops suffered from several years of bad weather and they were forced to use plants in pots. Nevertheless their results showed that the electro-cultural effect was real and promised substantial gains – but unfortunately that they were also highly erratic and very hard to control.

Meanwhile work in other countries including the US was less encouraging. The Department of Agriculture issued a bulletin in 1926 which concluded that ” a review of the literature of electrocultural experimentation up to the present time does not lend assurance of great progress.”

Ten years later in 1936 the British Electrocultural Committee was wound up concluding that there was “little advantage to continue the work either on economic or on scientific grounds… and regret that after so exhaustive a study of this matter the practical results should be so disappointing.”

So electro-culture was clearly now seen officially as a curious but unreliable phenomenon and pursuing it a waste of time, and once again interest in it faded away. However, David Kinahan, of the Department of Science and Technology Studies, at University College London, who has researched the committee’s work came up with another interesting fact or two. He discovered in the National Archives that although their annual reports contain many positive facts these were never made public because from 1922 onwards their reports were all marked ‘not for publication’ with only two copies ever printed – one for the minister and another for the archives. Although the work was not a classified secret he was unable to ascertain why effectively the committee’s findings should have been suppressed like this. Anyone got any thoughts on that?

Things were definitely not secret in France where Justin Christofleau, an engineer and inventor wanted do away with chemical fertilisers but still improve plant growth, rejuvenate old plants and deal with many pests and diseases. He experimented in his own potager électrique, or electric vegetable garden using what he called “electro-magnetic terro-celestial” power. It was well reported in gardening and even national press and he travelled the world lecturing eventually writing it all up in Electroculture which was also translated into English.

More than that, he patented several devices which went into commercial production. Despite being persecuted for his inventions by lobbyists from the agro-chemical sector, over 150,000 of them were sold before war broke out in 1939 and closed the factory. Christofleau still commands a lot of interest and, although he died in 1938, has his own Facebook page and an official archive.

As a result of all the work of these early researchers there was plenty of evidence, even if of variable quality, and they kept asking the question how can we make this work better?

But there was no convincing answer as to why electricity had these effects.

There were all sorts of theories but no certainty until the great Indian plant physiologist Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose devised incredibly sensitive equipment to prove that plants respond physically, in the same way as animals, to electrical impulses. This was written up in a series of books including Response in the living and non-living [1902] Comparative electro-physiology (1907) and The motor mechanism of plants (1928)

However, despite further research it was not until 2006 that Andrew Goldsworthy, a plant biotechnologist from Imperial College, put forward what seems like the most likely explanation for what actually caused this reaction. He showed that what is seen in Electro-Cultural experiments is a plant’s natural reaction to a brewing thunderstorm.

Physicists, meteorologists and other scientists please excuse my poor attempt at summarising what I think that means…

Plants need water so plants in dryer location gain an evolutionary advantage if they can quickly maximise their use of sudden downpours, such as produced in a thunderstorm, before it soaks away. Thunderstorms carry an electrical charge and somehow plants have learned to read that as a signal that heavy rain is imminent. What lab experiments showed was that the optimum electrical charge to be applied to plants to increase yield turned out to be similar to the charge in a thunderstorm. When it receives the charge a plant activates genes and speeds up its metabolism which includes increasing the rate at which roots can absorb water and thus encouraging growth etc.

So, if as this suggests, the electrocultural effect everyone has investigating is a simple physiological response, then why I wonder aren’t our fields full of apparatus designed to fool plants into thinking there was about to be a thunderstorm?

So, if as this suggests, the electrocultural effect everyone has investigating is a simple physiological response, then why I wonder aren’t our fields full of apparatus designed to fool plants into thinking there was about to be a thunderstorm?

That was like opening a huge can of worms because … there are those who think its all a bit hippy, new age pseudo-science allied to ley lines, pyramids and crystals – and those who are passionate believers in the possibilities. China, for example, has become the biggest protagonist with 3,600 hectares (8,895 acres) of “electrified” glasshouses already as can be seen in a 2018 report from the World Economic Forum

There definitely isn’t space to go into it all now and it would be very easy to get bogged down in the battle between conventional and non-conventional schools of thought so rather than suggest one or two starting points for further research as I usually do why not just try a simple google search for electro-culture and follow the sparks!

Pingback: Electroculture Gardening with Copper Antennas. What’s all the Fuss about? - tinysmartgarden.com

Pingback: Electroculture: What is it? - tinysmartgarden.com

Thanks for the mention.

David

Pingback: The Ultimate Guide to Electroculture - IronCabin

Thanks for the mention!

Pingback: The eccentric pioneers of vegetable electricity – Yerepouni Daily News

We are going to give it a go. I bought some good quality copper wiring to get us started. I hope it works out.

Good Luck!