I’ve just spent a couple of days visiting historic gardens around Cardiff, an area of the country that I did not know at all. One of them was Dyffryn, an Italianate mansion set in a splendid Edwardian garden designed by Thomas Mawson for the industrialist and coal magnate John Cory, and his plant-mad son Reginald.

But in this post I’m not going to rave about Dyffryn’s whole series of semi-secret small gardens, or the wonderful herbaceous borders, or the arboretum with its collection of champion trees, or even Reginald Cory’s plant hunting expeditions. Nor am I going to talk about the way the National Trust is involving the community in its plans for the house, or the enthusiasm of the garden team or even the delicious afternoon teas that are available. All that’s going to have to wait a little while…. and instead I’m going to talk about wisteria.

It’s not quite such a non-sequitur as you might think.

A few days before my visit I noticed that one of the many wisteria in my own garden has begun a second flush of flowers, and then wondered why I knew so little about them as a plant family, particularly as they play such a prominent role in many British gardens. Did you know, for example, that Chinese wisteria – Wisteria sinensis – twines its stems anti-clockwise, while Japanese wisteria – Wisteria floribunda – grows clockwise?

The mansion at Dyffryn has a colonnaded and balconied entrance on the garden front, planted with wisteria and it too had a few splashes of colour from repeat flowering. Cory’s bedroom opened directly onto the balcony and gave him long views down the main axis of the garden. Although the house is now almost completely empty, his former bedroom walls had series of paintings by Edith Adie of the gardens in their heyday in 1923…. and there were wisterias everywhere….. so what better excuse to do some research?

The wisteria has been around a long time. Fossils at least 7 million years old have been found in China [Wang, Q. et al, “Fruit and leaflets of Wisteria… from the Miocene”, International Journal of Plant Sciences, 2006 167:1061–1074.] but despite that they only came to European notice in the last 300 years.

Wisterias originated in 3 main locations in the world. The two more obvious ones are China and Japan but the first specimens to reach Europe came from Mark Catesby who was collecting plants in Carolina in 1724. Now known as Wisteria frutescens it was named Glycine frutescens by Linnaeus in Species Plantorum (1754), the starting point for modern botanical nomenclature. In many early nursery catalogues it was known as the Carolina Kidney Bean in because its spotted seeds were thought to resemble very small kidney beans. Wisteria frutescens doesn’t have the same widespread appeal as its Asiatic cousins, probably because its sprays of flowers – technically its racemes – are much smaller and less fragrant. This might be set to change as, with the trend to smaller and smaller gardens, breeders have developed a variety suitable for containers. This is now widely available as “Amethyst Falls”.

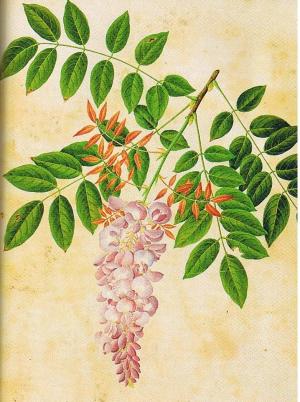

Wisteria sinensis by John Reeves, from the Reeves Colelction of Chinese drawings, vol.2 No.64, Lindley Library, RHS.

Much more popular is the chinese wisteria, wisteria sinensis. The first European to mention it was a French Jesuit missionary, Domenic Parennin in the early 18thc who described “the climbing plant teng lo with beautiful violet flowers hanging down in large bunches”. But it was not actually seen in Europe until 1816. It was probably sent by John Reeves who worked for the East India Company in their base near Canton who had acquired it from the garden of a local Chinese merchant whose anglicised name was Consequa. Another specimen, from the same garden source, arrived a few days later on another East Indiaman. This one was given to Thomas Palmer of Bromley.

The authoritative Curtis’s Botanical Magazine has a long entry in 1819 discussing its classification before naming it Glycene sinensis, and then describing the plant and its arrival.The botanist Thomas Nuttall reclassified it as Wistaria after Caspar Wistar, a Philadelphia doctor, or just possibly after his friend Charles Jones Wister. In earlier texts it is usually spelled with an ‘a’ but more modern sources use an ‘e’. You pays your money and you takes your choice.

To be honest,tough though wisterias are, it’s amazing the first one survived given how it was treated!

Wisteria sinensis then known as Glycine sinensis, tab 2038, from Curtis’s Botanical magazine, vol,46, 1817-8

In 1826 the Transactions of the Horticultural Society included a detailed article by Joseph Sabine about the early history in cultivation. The first newly propagated plants had been given to the Horticultural Society, and to a Lady Long of Bromley, as well as to two commercial nurseries, Loddidges in Hackney and Lee’s in Hammersmith. Already the plant’s tough qualities were being noticed: “It does not require any nicety of management” and “it is impatient of the knife”. Although at least one of the specimens was being grown under glass it had survived harsh winters and was clearly ” a hardy shrub in our climate” and “among our best ornamental shrubs”. If you want to read Sabine’s article in full it can be downloaded from: http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/14330#page/161/mode/1up

Fullers Brewery in Chiswick, west London claims to have the oldest surviving specimen in Britain growing on their former head brewers cottage wall: see

John indley from Makers of British Botany http://www.archive.org/details/makersofbritishb00oliv

By 1840 the Horticultural Society’s specimen “was an object of great attention” and John Lindley, the society’s secretary was obviously impressed.[or slightly crazy?] He used it as “as evidence…of the creative power of Nature”, calculating that “the number of branches was about 9000 and of flowers 675,000. Each flower consisting of 5 petals, the number of these parts was 3,375,000” and continued through ovaries, ovules and seeds to explain that the plant had 27 billion grains of pollen and “that all the petals been laid end to end they would have extended to a distance of more than thirty four miles.”

1844 saw the “discovery” of the white form – wisteria sinensis alba – in a garden by Robert Fortune, who was able to get permission to take layers from it, and by 1847 a specimen was growing in the Horticultural Society/’s garden in Chiswick.

Wisteria expert Peter Valder says that after this there were very few new introductions of wisterias from China, and that whereas Japanese nurserymen realised there was a market for their plants abroad and even produced catalogues, their Chinese counterparts showed no interest. The likelihood is therefore that until very recently most of the wisteria sinensis grown in Europe came from the same very limited genetic stock, but Valder notes that on plants he had seen in cultivation in several Chinese cities “no two plants appeared to be the same’ so that there is hope for a lot of further hybridization. [For more information see Peter Valder, Wisterias: A Comprehensive Guide, [Balmain, Australia, 1995]

Our third source for garden wisterias, Japan, is better appreciated and understood. There are two species indigenous to the Japanese archipelago: Wisteria brachybotrys and the better known Wisteria floribunda. They have both been esteemed, recorded and hybridized for centuries by the Japanese, even featuring in literature and poetry as early as the 8th century. Yet, even more than China, Japan was isolated, deliberately so, from the west. Indeed from 1638 until 1858 Japan was closed to foreigners and the Japanese themselves forbidden to travel overseas. Only a single tiny Dutch trading outpost was allowed, on an artificial island in the harbour of Nagasaki where the handful of inhabitants were closely monitored and all contact with the Japanese strictly regulated. There is a very readable fictional account of life there in David Mitchell’s The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet (20xx).

Our third source for garden wisterias, Japan, is better appreciated and understood. There are two species indigenous to the Japanese archipelago: Wisteria brachybotrys and the better known Wisteria floribunda. They have both been esteemed, recorded and hybridized for centuries by the Japanese, even featuring in literature and poetry as early as the 8th century. Yet, even more than China, Japan was isolated, deliberately so, from the west. Indeed from 1638 until 1858 Japan was closed to foreigners and the Japanese themselves forbidden to travel overseas. Only a single tiny Dutch trading outpost was allowed, on an artificial island in the harbour of Nagasaki where the handful of inhabitants were closely monitored and all contact with the Japanese strictly regulated. There is a very readable fictional account of life there in David Mitchell’s The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet (20xx).

It is only through the work of 3 physicians to the trading posts [all later remembered in the names of plant species] that any knowledge of Japanese plants and gardens reached Europe. Engelbert Kaempfer was there from 1690-92 and published his account of Japan including many plants in 1712 – amongst them the two species of wisteria or Too Fudsi and Jamma Fudsi as he called them. Nearly a century later Carl Thunberg became the trading post’s doctor, and on his return published Flora Japonica in 1794. Later still, in the 1820s, Phillip von Siebold managed to send back both herbarium and living specimens but the Japanese wisteria – Wisteria floribunda – was probably not introduced into cultivation until 1830 in America and probably even later in Europe. It was only after the enforced opening of Japan to western trade after Commodore Perry’s expedition that further introductions took place.

The fact that the Chinese and Japanese wisterias did not reach England until the 19thc did not stop them quickly achieving a special place in the English garden. As early as 1872, writing in The Garden William Robinson described them as “among our most common and valued climbers”. The following year a full page illustration of Salt Hill hotel at Slough proved the point. But because they were new introductions they were not always planted wisely. Gertrude Jekyll commented on this “odd misuse of a fine plant” in her book Gardens for Small Country Houses in 1913.

But because they were new introductions they were not always planted wisely. Gertrude Jekyll commented on this “odd misuse of a fine plant” in her book Gardens for Small Country Houses in 1913.

The wisteria at Carnwath House, Fulham which grew through the floor and departed through the wall! from Philip Davies, Lost London 1870-1945, English Heritage.

An even worse case was the wisteria planted at Carnwath House in Fulham. “This beautiful villa…commands a fine view of the Thames which flows within a few yards of the pleasure ground which are adorned with some fine cedars of Lebanon and other ornamental trees and shrubs [William Keane, The Beauties of Middlesex, 1850]. The house may have been the model for Sir Barnett Skittles villa in Dicken’s Dombey and Son….although I’m sure Sir Barnett did not have a wisteria planted quite so curiously as this one!

Wisterias are mentioned as specific features in 38 of the parks and gardens listed on our database, and over 60 of the gardens open under the National Gardens Scheme claim them as outstanding features, and while the main wisteria season is over there are still plenty of plants in flower to admire.

Wisteria sinensis alba at Sissinghurst

http://www.invectis.co.uk/sissing/sswall.htm

![Wisteria floribunda [then described as wisteria multijuga] from Louis Houtte, Flore des Serres, vol.19 1873](https://thegardenstrustblog.files.wordpress.com/2014/07/wisteria.png?w=640&h=502)

Pingback: “A Persian princess, a little Indian, a fox, a morning glory, a lovely wisteria–it always pleased them when you told them they looked like something, like something else.” – Year in the Quiet House

Thanks for the mention – good luck with your new life in Portugal – the photos look beautiful and it all sounds a great adventure as well. David

Pingback: Wisteria Lane (Makro Monday) – merlanne