![Araucaria araucana (Molina) K. Koch [as Araucaria imbricata Pavon] araucaria, Chilean pine, monkey puzzle tree Houtte, L. van, Flore des serres et des jardin de l’Europe, vol. 15: t. 1577 (1845)](https://thegardenstrustblog.files.wordpress.com/2015/10/147325.jpg?w=325&h=431)

Araucaria araucana

from Flore des serres et des jardin de l’Europe, v15

Ambrosio O’Higgins

1720-1801

Believe it or not it is all supposed to have begun with a banquet given in April 1795 by the wonderfully-named Ambrosio Bernardo O’Higgins, and an unusual dish that he served!

But of course you should never believe everything you’re told…

I’ve been researching araucaria for several years now intending to publish an article on its early history in Britain but was overtaken by David Gedye, who published a beautifully illustrated and very detailed history of Araucaria( the monkey puzzle’s botanical name) in 2019, based around his great-great-grandfather, Philip Frost who was head gardener at Dropmore where one of the earliest specimens was planted. Since I couldn’t compete with such a good book I thought I’d turn my research into blogposts of which this is the first.

I’ve been researching araucaria for several years now intending to publish an article on its early history in Britain but was overtaken by David Gedye, who published a beautifully illustrated and very detailed history of Araucaria( the monkey puzzle’s botanical name) in 2019, based around his great-great-grandfather, Philip Frost who was head gardener at Dropmore where one of the earliest specimens was planted. Since I couldn’t compete with such a good book I thought I’d turn my research into blogposts of which this is the first.

Irish-born O’Higgins was the Captain-General or military governor of Chile, which was then still a part of the Spanish empire. The dinner party he gave was in honour of Captain George Vancouver and the officers of HMS Discovery and HMS Chatham who were surveying the Pacific coast of the Americas for the British government in the 1790s. Amongst them was Archibald Menzies, a surgeon and the accredited botanist collecting plants for Sir Joseph Banks and the royal gardens at Kew.

Female cone and seeds

The story goes that some large nut-like seeds were served at dinner and because Menzies did not recognize them he pocketed a handful and took them back to the ship to try and grow them. They were from what the indigenous people called the peghuen tree, which is better known to us, of course, as the monkey puzzle.

This story does not appear in print until 1880, although it’s supposed to have been told by Menzies to William Hooker, Kew’s first director. However it’s unlikely to be totally accurate. Monkey puzzle seeds aren’t in crackable shells but wrapped inside leathery bracts that have to be cut open, and that’s best done by soaking them in hot water first – hardly conducive to successful germination! Unfortunately we can’t check with any evidence from Menzies himself since it’s not mentioned in surviving letters to Banks, and his journal where he might have noted the occasion has been lost. But it does make a good story.

An alternative, more prosaic and realistic version of how Menzies got the seeds is recounted by Aylmer Lambert, the President of the Linnean Society, of which Menzies was a member. In his book A description of the genus Pinus published in 1832 Lambert has a drawing of a male monkey puzzle cone which came from a specimen [now in the Natural History Museum] collected by Menzies. There is no drawing of a female cone but since as you can see they disintegrate as they ripen, it seems more likely that Menzies could only bring back a male cone for Lambert, andnkept the seeds from a female cone that had fallen to pieces. However since he certainly didn’t go to the mountainous southern area where the trees grow we have no way of knowing exactly how he might have obtained them.

Th e seed needs to be sown either flat on the surface or pushed in at a slight angle

It’s at this point that we really have to take our hats off to Archibald Menzies because notwithstanding all the difficulties he managed to get some seeds to germinate in a rudimentary cold frame on the ship’s quarter deck on the voyage home. They must have been fresh since they quickly lose viability and he must have had not only green fingers but the right knowledge about precisely how to sow them.

Monkey puzzle seeds are big – up to 2″ or 5cm long – and need to be planted longways on, with just one end pushed into the soil rather than buried or even lightly covered as with most seeds. Somehow Menzies managed and, although we don’t know how many he actually planted, there were still had 5 healthy seedlings by the time the expedition returned to England at the end of the 1796. It’s unlikely any other seed he bought back would have been viable after this time.

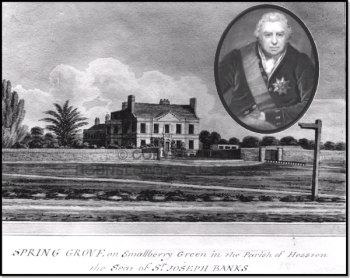

Spring Grove at Heston, home of Sir Joseph Banks

Hounslow Local Studies Library

The seedlings, which can only have been a couple of inches high, were given to Joseph Banks who planted one in his garden at Spring Grove at Heston where it soon died, while the others were sent to Kew. Initially named Sir Joseph Bank’s Pine, one of them was planted outside where it too soon died. The others were now regarded as tender specimens and kept in a greenhouse until 1808 when another one was trialled outside over winter protected by a temporary shelter and proved totally hardy.

I wrote recently about late 18th/early 19thc contract gardeners who rented out plants to decorate grand houses and gardens for parties. Kew was at this stage still a private royal garden and it seems as if the Prince Regent might have treated its collection as a source for house decoration. “The most magnificent specimen of Chili Pine (Araucaria imbricate) at Kew Gardens” was, according to Patrick Neil, secretary of the Caledonian Horticultural Society, borrowed for decoration at a banquet at Carlton House. It was returned “irretrievably injured… owing to the servants having very imprudently attached lamps to the branches.”

Another of the original Menzies seedlings “which had previously been kept in a greenhouse was presented by King William IV to Lady Grenville for her collection at Dropmore, not that far from Windsor. It was then about 5 feet high and growing soon a tub.” By 1876 when it was featured in The Garden it was recorded as being in good health and 60ft tall.

Queen Victoria visiting Dropmore in 1840 admired the tree and asked William Hooker for a monkey puzzle for Prince Albert. It’s likely that he was given the one that survived the Carlton House party, although it did not do well after it was plan ted at Windsor and was later replaced.

These introductions by Menzies proved to be the start of the British love affair with the the monkey puzzle or Araucaria araucana as it is more properly known.

Of course, Menzies wasn’t the first European to ‘discover’ the araucaria. They had first been noticed by Spanish explorers in southern Chile in the mid-1600s, but did not really command much attention until the later 18thc. In 1780 Don Francisco Dendariarena was employed by the Spanish government to investigate the forests of central Chile – the country of the Araucanos people – to see if any of the trees were suitable for shipbuilding and ship repairs. Unfortunately he decided the monkey puzzle would be a good bet. I say unfortunately because, as a result, araucaria became most valuable timber in the southern Andes, used not only for ships but also railway sleepers, pit props, and paper pulp. Wholesale logging eventually devastated the forests and eventually put araucaria on the endangered list, despite it becoming the national tree of Chile.

![Araucaria araucana (Molina) K. Koch [as Araucaria dombeyi A. Rich.] araucaria, Chilean pine, monkey puzzle tree Richard, L.C.M., Commentatio botanica de Conifereis et Cycadeis, t. 20 (1826) [L.C.M. Richard]](https://thegardenstrustblog.files.wordpress.com/2015/10/271017.jpg?w=325&h=451)

Araucaria araucana [as Araucaria dombeyi ] from

LCM Richard, Commentatio botanica de Conifereis et Cycadeis, t. 20 (1826)

The first description of them – as Pinus araucana was published by a Chilean Jesuit priest, Juan Molina, in exile in Italy in 1782, in his account of Chile’s natural history Saggio sulla Storia Naturale del Chili. However, probably unknown to him, the Spanish government had earlier commissioned three botanists – two Spanish – Joseph Pavon and Hippolito Ruiz and one French – Joseph Dombey – to survey the natural history of Peru and Chile.

They arrived in South America in 1778 and Pavon & Ruiz were there for more than 10 years. Pavon discovered the araucaria in September 1782 and when Dombey returned to France he took specimens to the Jardin Royale in Paris where they were examined by both Lamarck and Jussieu – the leading botanists and taxonomists of the day. They disagreed. Lamarck named the plant Dombeya chilensis while Jussieu preferred Araucaria.

In 1797 Ruiz and Pavon published their findings -in Florae Peruvianae et Chilensis prodromus [which as you might guess from the title was in Latin] in which it was listed under Dombeya, although all the other variations were also included. Quite what else was being said is difficult to determine as I failed Latin ‘O’ level twice but if yours is better then follow the link to check for yourself.

Pavon also sent more seeds and herbarium specimens to the Jardin des Plantes in Paris.Later he was to write a paper for Royal Academy of Sciences in Madrid which listed many errors in both Lamarck’s and Jussieu’s descriptions of the specimens, with derisive comments such “he made no use of …my [accompanying] description” ..and “I omit their other mistakes” opting instead for the use of Molina’s designation instead of either of the French versions.

So the poor old peghuen tree had already got 3 new names, all disputed. If it had stopped there then it wouldn’t have been too bad …

It soon had at least two more! Richard Salisbury seems to have renamed it Columbea quadrifaria in 1807 in the Transactions of the Linnean Society, although without explanation so quite why I’m not sure.

But then in 1813 William Aiton’s Hortus Kewensis, (Vol.5 ) called it Araucaria imbricata citing the German botanist Willdenow of Berlin Botanic Gardens who had named it that in 1797. And in England at least that’s the name that stuck for a while.

[I told you it was complicated!]

When the first English account was published in Aylmer Lambert’s A description of the genus Pinus in 1824 the author took no chances and listed all three names but uses Araucaria imbricata on the accompanying plate. This includes several drawings made from the specimens brought back by Menzies which were then in the Banks herbarium. Lambert adds that “the only plants of this species, in the country, are those contained in the Royal garden at Kew; they were raised from seeds brought home by Mr Menzies. One of these trees planted in the open ground is now 12 feet high, and seems perfectly hardy.”

News about these new and bizarre-looking trees spread helped of course by our old friend, John Claudius Loudon. In his comprehensive Encyclopaedia of Gardening of 1825 he commented on the state of gardening in every corner of the globe, including South America.

So far I’ve only talked about the seedlings brought back by Archibald Menzies so how did the monkey puzzle get in wider circulation? The standard story is that it was James Veitch, the famous Exeter nurseryman, who was first responsible for its widespread distribution in Britain, using the seed collected by William Lobb who he sent out to South America in 1840.

Robbie Blackhall-Miles writing in The Guardian in 2015 claimed that monkey puzzles “continued to remain rare in British gardens until well past the turn of the 19th century and were grown only by the elite, who prized them as symbols of status and wealth. That is, until James Veitch employed William Lobb to collect seed for his nursery and in 1843 the first monkey puzzles went on general sale for £10 (equivalent to £880 today) for 100 seedlings. This move by Veitch and their subsequent sale by other nurseries made the trees more accessible”.

Matthew Biggs, for example, writing in The Garden in June 2014 agrees, saying that “James Veitch seems to have been the first to spot the ornamental potential of Araucaria araucana, and …the 3,000 seeds Lobb harvested helped ensure the rise of monkey puzzle trees to fashionable status symbols.” Matthew Wilson in the Financial Times 5 July 2013 says much the same.

While I hate to disagree with such eminent horticulturists I’m afraid they’re way off the mark.

It’s absolutely true of course that Veitch was an enterprising and astute judge of gardening tastes and trends, and that, having seen the araucaria growing at Kew, he realised it was a winner. Although Lobb was sent on a general plant hunt for anything that he thought might be useful for the English market, it’s also true he was given explicit instructions to collect as much viable seed of araucaria as possible. But it simply is not true that Lobb was the first to collect it in quantity after Menzies, or that Veitch was anything like the first to introduce it into commercial production.

Araucaria reaching the tree line at c. 1500 m on the Sendero Sierra Nevada, Conguillío National Park, Chile. Image Tom Christian.

So where does this story come from? The answer is, as is so often the case from the victor in the propaganda war: in this case the Veitch nursery themselves. Hortus Veitchii the company history says that Lobb collected large quantities of seed and “was thus instrumental in bringing this remarkable Conifer into general use for ornamental planting.”

But if you go back and read that extract from Loudon’s 1825 edition of his Encyclopedia of Gardening again. Its very clear: “there are now a number of collectors in that country for the purposes of botany and horticulture”. Who they were, where their finds ended up, and why it’s called a monkey puzzle tree we’ll see in another post shortly…

You must be logged in to post a comment.