Japanese culture, plants and gardens took the western world by surprise – and by storm – in the second half of the 19th century.

But how did that happen to a country which had been in virtually total isolation for 220 years?

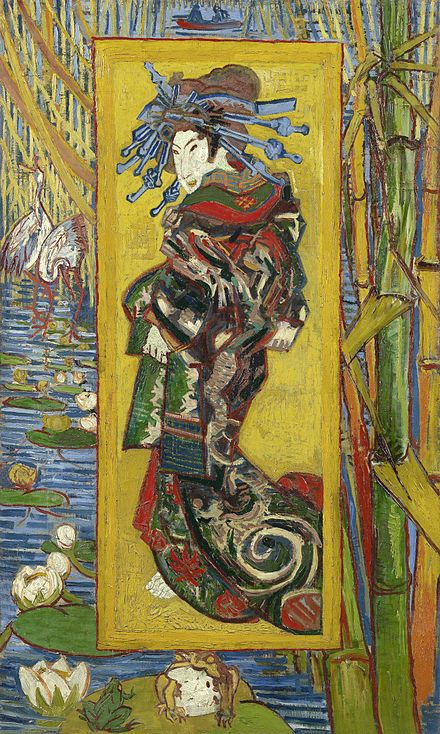

Where did Van Gogh get his inspiration for this painting?

What’s it got to do with cheap packing material?

With an English architect?

With “Black Ships”?

or with big public events in Paris, Vienna, Philadelphia and Chicago?

Read on to find out…

Last week’s post explained how from 1633 Japan had virtually closed its doors to all foreigners and went into self-imposed and self-controlled isolation. Unfortunately by the early 19th century western commercial interests wanted access to its markets, and tried all sorts of diplomatic ways to get Japan to open its ports to trade. When that didn’t work, in 1853 they turned to other means, just as they had done with China a few years earlier.

The Americans sent over a small fleet – called the Black Ships by the Japanese – under Commodore Matthew Perry to try once more. He was told that if the negotiations failed he was to use force. The threat worked and in 1854 the Japanese signed a treaty opening two ports to the Americans. It was then only a matter of time before the other western powers followed suit and Japan’s 220 year isolation ended.

Almost instantly diplomats, businessmen, nurserymen and even the first adventurous tourists flocked in from both Europe and North America. It was as if Japan was the final frontier on the globe and very quickly all things Japanese – including its plants and gardens – took the western world by storm. Turning the situation to their own advantage, and greatly aided by the new phenomenon of the International Exhibition Japan began to put itself on show, and what a show it was.

Of course as we saw last week Japan’s isolation wasn’t total. The Dutch base at Deshima allowed glimpses into Japan’s culture and plants also very slowly made their way to Europe. But as soon as the restrictions were lifted Japan began to influence the west.

One of the first signs was the use of cheap prints as packing material around export ceramics and furniture. Some of these were found in Paris by the artist Felix Braquemond in 1856, depicting flowers and other natural history subjects. They included some by the now globally famous Katsushika Hokusai who made woodcuts based on everyday life, usually known as Ukiyo-e, or Pictures of a Floating World.

It was a discovery that was to change the direction of western art well into the next century.

Japan first went on show at the universal exhibition in London in 1862. On display were a few hundred Japanese objects in porcelain, bronze, lacquer, and bamboo collected by Sir Rutherford Alcock who was Britain’s first Consul-General and Minister Plenipotentiary to Japan between 1858 and 1865. Although this was a significant event the objects he chose for the exhibition showed the country through European rather than Japanese eyes.

What was probably more significant was that the exhibition was visited many times by the Japanese diplomats, the first such major public event that had ever seen a Japanese presence. In this their first sight of the “best of the west” the Japanese were not so much interested in western culture as in machinery and technology, and they ended up visiting a telegraph station, a naval shipyard, a dockyard and a firearms factory.

These choices were the direct result of what the Japanese rightly saw as Unequal Treaties which led leading figures in what was still a very hierarchical feudal system to declare “if we take the initiative, we can dominate; if we do not, we will be dominated”. It was the first step towards Japan adopting and improving western technology, and taking its place as a leading industrial country.

In 1863 Alcock published The Capital of a Tycoon, a 2 volume memoir of his time in Japan and there’s a section on Japanese plants and gardens. This was not written by Sir Rutherford himself but by John Veitch, who was the first important plant hunter to enter Japan. [More on him soon]

In 1867 France was to play host to the Exposition Universelle in Paris. The previous year Emperor Napoleon III invited the shogun of Japan to not only have a pavilion at the exhibition but to attend himself.

In the end Japan sent the shogun’s 14 year old brother Tokugawa Akitake instead, and a detailed journal of the mission was kept by his secretary, showing he later travelled round Europe absorbing western ideas and meeting monarchs including Queen Victoria and William III of the Netherlands before returning to Japan in 1868.

The items exhibited in the Japanese pavilion were the first chosen by the Japanese themselves and were mainly fairly conventional artefacts, but they also included a tea shop where visitors could see Japanese women relaxing and smoking pipes. There was also a display of prints by Hiroshige which caused a real stir in the artistic world.

Monet for example had a copy of Hiroshige’s print of a wisteria over water at Kameido, and its seems likely that the bridge over his lake of waterlilies was inspired by that and other prints he saw at the exhibition and collected afterwards.

One of the Japanese pavilions at the 1867 Paris Exhibition French National Archives. F/12/11871/2.

At the end of the exhibition the Japanese exhibits were sold off, with most all of them remaining in France where they circulated amongst collectors and led to a new trade developing in Japanese artefacts.

From then on there was much wider availability of Japanese woodblock prints along with ceramics, furniture, jewellery, and textiles. This also led to a new word being invented in France to describe Japan’s sudden fashionability: Japonisme.

The Flowering Plum Orchard by Hiroshige from the Rijksmuseum and Van Gogh’s version of it in the Van Gogh Museum

Japonisme has been written about widely, and it is clear it affected almost every artist of the period that you heard of from the 1860s onwards. Rather than go through all of them I’ll add some references at the end and just mention two of those who fell for Japan the most.

Van Gogh began by collecting the work of earlier artists who had been influenced but then in 1885 began collecting original Japanese woodcuts, copying them, adapting them and using them as backgrounds in his portraits and even organising an exhibition of Japanese prints in 1887. He said “All my work is based to some extent on Japanese art.”

Pierre Bonnard, was another highly influenced by Japanese art. Amongst his works were a set of four narrow vertical panels, initially intended to be part of a Japanese-style folding screen, showing women in stylized garden settings. The subject as well as the detailed patterns and flat decorative forms were directly inspired by Japanese prints and painted screens.

For more on this good places to start are:”Inspiration from Japan” on the Van Gogh Museum website; “Japonisme” and also “The Great Wave: The Influence of Japanese Woodcuts on French Prints” by Colta Ives on the Metropolitan Museum of Art website.

While this was going on in Europe political events in Japan were moving very rapidly. There was an upheaval, overthrowing the feudal shogunate and bringing the “modernising” Meiji emperor to the throne in 1868.

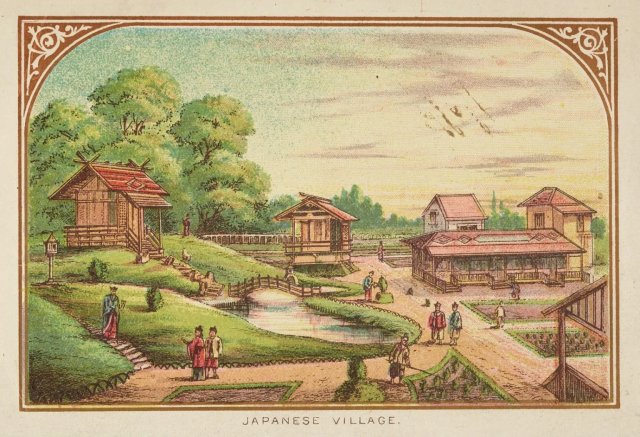

From then on Japan participated in all the major world exhibitions, although in the early days taking advice from western friends. The first was the Vienna International Exposition of 1873 where the son of Philip von Siebold [see last week’s post for more on him] and another German Carl Wagener helped choose how Japan should portray itself. They opted for traditional crafts, although even by this stage they were often being mass-produced for export.

They also played on Japan’s continued “exotic” appeal and decided to use architure to capture that, building a village which included a Shinto shrine, a traditional music and dance hall, an arched bridge and a Japanese garden featuring a white wooden gate. Meigs was intrigued rather than attracted: “The queer cane fence, and general disposition of the pools, stone and clay figures, and other ornaments, gave this place a most interesting appearance. The taste displayed in these garden buildings was well worth study and report.”

from Cortazzi’s article

As Siebold and Wagener expected, the Japanese village and gardens received great acclaim. It was so highly regarded by the designer Christopher Dresser, who had founded the Alexandra Park Company in 1873, that the buildings, and even the trees and stones which had been imported especially from Japan, were bought by the company for £600 and transferred to the grounds of Alexandra Palace in north London. It was the first Japanese designed gardens to be seen in Britain.

There’s much more information about the Japanese Garden at Alexandra Palace in an article by Hugh Cortazzi in the Japanese Garden Society Journal

Not all of the reaction was, however, that favourable!

It was America’s turn to be wowed next. In 1876 there was a World Fair in Philadelphia to mark the 100th anniversary of US Independence. Huge amounts of money were spent by the Japanese government, and their exhibits were overseen by Tokugawa Akitake. One of the buildings was described as a “pagoda”, although it wasn’t – and in fact it was designed and made in Norwich! Like the village from the Vienna exhibition it ended up back in Britain: in Chapelfield Park in Norwich to be precise.

For the story of how it got there take a look at Jeckyll and the sunflower motif and“Do you remember the extravagant two-storey pagoda which was in a busy park?”

Shofuso

Although the building later burned down the site of the Fair was converted into Fairmount Park and in 1958 as a sign of post-war reconciliation a new Japanese pavilion, called Shofuso was moved there and put up in its stead.

Archaeology has recently been undertaken to discover what remained of the original pavilion.

1876 is also significant because it was also the year that the British architect Josiah Conder first went to Japan. Conder had worked for the the great Victorian architect William Burgess, who was the foremost medievalist in the architectural profession and, since the London exhibition of 1862 had also developed a keen interest in Japan. Conder had just been awarded the Soane medal when he was approached by the reformist Meiji administration and asked to become professor of architecture at the newly founded Imperial College of Engineering. This was a pioneering institution at the forefront of transforming Japan’s systems and infrastructure, and Conder’s job was to teach the first generation of Japanese architects in the Western tradition, and later he became architect for many of the country’s new public works projects.

Conder was soon totally absorbed by and committed Japanese culture. He settled permanently in Japan and married a Japanese woman. In the 1890s he published three books: The Flowers of Japan and the Art of Floral Arrangement(1891), Landscape Gardening in Japan (1893), The Floral Art of Japan (1899), We’ll return to them in another post soon.

By the time these books came out there had been several more international exhibitions all of which featured a rapidly modernising Japan.

A third Paris Exposition was held in 1878, where Japan’s pavilion was “a breath of fresh air … a crystalline sound of falling water comes to your ear. This fresh murmur of a spring originates from two small flowerbeds where pretty earthenware fountains stand; they themselves have the shape of large flowers, of water lilies with large open hearts, from the orifice between their elongated pistils come thin streams of liquid silver in beautifully tiered conch shells. The upper basin holds small bamboo goblets fitted with a thin, long stem for the passer-by to enjoy. In the ground-level basin which is surrounded by a belt of decorative pebbles, crustaceans and amphibians made of glazed terracotta sleep and crawl. Water, flowers, a strange decor, hospitable attention: that is Japan! [Gazette des beaux-arts, Nov 1878]

The exhibition spread over several sites, and in the gardens around the Palais du Trocadéro there was a Japanese farm and large garden with plants bought from Japan at the end of the previous year. One reporter explained : ” I do not really have the time to elaborate here on all the exotic samples of plants and birds that the Japanese show us in these tiny zoological gardens, but … The small Japanese farm, with its gate, its fences, its tiny flowerbeds, its spindly plants, its bamboo house, and with all the unexpected of an exquisite art, discreet, refined, [and] original, remains one of the wonders of the Exhibition.” [Gazette des beaux-arts, Dec 1878]

It was also the first time that Bonsai had been exhibited outside Japan. These caused a sensation and were written up enthusiastically in the Revue Horticole, the main French gardening magazine of the time.

Another sign of the influence of Japan can be guessed at because there was also a show of paintings by Félix Régamey who had made a ten-month trip to the Far East with Émile Guimet (the collector and founder of the Musee Guimet ). They followed that up with a couple of books.

from the Bibliotheque national de France

A fourth Paris expo followed in 1889 again with a Japanese garden, at the Trocadero surrounded by a bamboo fence, with a bamboo kiosk, dry pools, and small rustic bridges made of tree trunk slices. There was also another exhibition of bonsai.

![]()

The Chicago Fair saw the first significant display of Japanese Bonsai in America, probably supplied by what was to become the Yokohama Nursery. It stood in the garden around the pavilion and caused quite a reaction not always favourable. Liberty Hyde Bailey [whose collection of nursery catalogues and other gardening books is now on Archive.org] wrote in Garden and Forest that “This Japanese garden cannot be called beautiful, as Americans understand rural art, but it is curious and grotesque.”

For me the most surprising thing has been that despite all the interest there are very few illustrations of, firstly what these exhibition gardens were like, and secondly what actual Japanese gardens were like and that includes in all the hundreds if not thousands of Japanese woodblocks I’ve looked at. Even when it seems the scene includes a garden it is usually just a sketchy landscape or perhaps some sketchy plants or flowers with a lot of blank space and very little sense of structure or layout. However, while such abstraction might have reduced public interest, what really put Japan into western gardens was the tsunami of plants that reached Europe sent back by the plant hunters who were sent out by commercial nurseries… more on that shortly

For more information on Japan and World Fairs there’s plenty out there on each fair separately but for a general introduction a good place to start is “Japan at the World’s Fairs: A Reflection” on researchgate,

You must be logged in to post a comment.