Details of tulips and anemones from Les Velins du Roi by Nicolas Robert, Museum of Natural History, Paris

I’ve been doing some research over the past few years into the gardening interests of the aristocratic Hatton family in the early modern period. They were prominent royalists and had extensive estates in Northamptonshire around Kirby Hall.

One of things that has emerged strongly is the way in which gardening and plant collecting were, [as indeed they still often are] activities that transcended all sorts of barriers. They allowed men [and occasionally even women] from completely different social, economic and cultural backgrounds to find common ground in gardens and plants, in a way that few other interests could be shared across such disparate groups.

Today’s post is proof of that. It is centred on a single letter – one amongst thousands – in the Hatton archives in the British Library. Read on to be surprised not so much by its contents but its writer and its recipient.British Library Additional Manuscript 29569 ff.212 and 213 [to give them their official designation] are two scrappy bits of paper – one a letter and the other the ‘envelope’ or wrapper in which it was sealed and which carried the address.

The letter was sent to Monsieur Simond Smyth at a house opposite La Belle Chasse [which I presume was an inn] in the Rue St Dominic in the Faubourg St Germain in Paris. The faubourg [or suburb] was just beginning to become the favorite home of the French nobility with many grand mansions being built in the new streets across the former open fields outside the city walls.

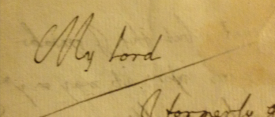

However the letter does not begin Dear or Honoured sir or Dear Mr Smyth or anything like that as one might expect. Instead it opens “My Lord” so you will probably not be surprised to hear that Smyth is a pseudonym.

The book imprint of Lord Hatton

https://armorial.library.utoronto.ca/stamp-owners/HAT005

Although the letter is dated September 7th, there is no year specified but, from other evidence, it was probably in the mid-1650s. This was several years after the end of the Civil War and when a large number of royalists had, like the future Charles II, gone into exile on the continent. Paris, where Henrietta Maria, Charles I’s widow was living, became one of the main centres for them. So it would be a reasonable assumption that the letter was addressed to an English exile, as indeed it was. But this was no ordinary royalist exile. Instead the recipient was a very prominent one: Christopher, Lord Hatton, who had been Comptroller of the Household for Charles I.

By now of course, given that this is a blog about garden history you will not be surprised to know the letter was about matters horticultural.

Hatton’s correspondent runs through a range of subjects that clearly have been the subject of other letters. Sadly, as far as I can see, none of these have survived.

The writer talks about a scheme to help set up a young gardener in business, about various plant catalogues they had seen or would like Hatton to obtain for them in France, about a book that they have been sent that has marginal notes about the plants in someone else’s collection, and a list of unusual plants they want Hatton to try and find and send over to the writer in England.

“The anemones they are by the description of their colours so rare and unknown here as I shall desire your lordship to add what more to them you judge fit and also the saintly irises; and for the tulips I chiefly desire the praecox, and that I may know the prices of the dearest before your lordship come to make a contract.”

![The Luxembourg Palace and garden [then known officially as the Orleans Palace], from Diverses vues d'endroits remarquables d'Italie et de France, Stefano di Bello, 1650](https://thegardenstrustblog.files.wordpress.com/2015/06/dp827796.jpg?w=375&h=201)

The Luxembourg Palace and garden [then known officially as the Orleans Palace], from Diverses vues d’endroits remarquables d’Italie et de France, Stefano di Bello, 1650

In return the writer offered Lord Hatton half a dozen plants which were neither in the catalogues of the gardens of the Duke of Orleans or Monsieur Morin. “If they be strangers your Lordship may command them.”

The garden of Pierre Morin in the faubourg St Germain, drawn in 1649 by Richard Symonds. BL Harley Ms 1278 f.81v

taken from Prudence Leith Ross

The Duke of Orleans, Louis XIV’s uncle, was a typical cultivated member of the elite. Apart from building an art collection and a cabinet of curiosities he was interested in the natural sciences. He divided his time between the Luxembourg Palace in Paris which had spectacular gardens designed by Jacques Bercau in the 1640s, and the royal chateau in Blois where he created a botanic garden filled with rare plants, as well as a menagerie and aviary. He was also a patron of the artist Nicolas Robert whose botanical images can be seen above.

Pierre Morin was one of the leading nurserymen of his day. He specialised in the kinds of flowers wanted by the writer. These were listed in his catalogues, the first of which was issued in 1651. There were 100 named varieties of tulip, 71 bulbous iris, and 27 sorts of anemones. [For more on Morin and his nursery see Prudence Leith-Ross, A Seventeenth-Century Paris Garden, in Garden History, Vol.21, No.2 pp150-157.]

Perhaps there would nothing unusual about that if it came from a fellow royalist sympathiser or old friend of Hatton …BUT …. Simon[d] Smyth was the main pseudonym used in letters between Hatton and Edward Nicholas, the future Charles II’s Secretary of State who maintained a wide network of correspondents often for intelligence purposes. However it was obviously known to others… including the Cromwellian government.

The letter ends that by stating that Hatton may “command the writer with anything in the writers power” and “begs yr pardon for this great confidence and remains yr lordships very humble servant.”

It is signed J Lambert.

John Lambert was a Parliamentary general at the age of 29 and became a leading political figure during the Protectorate. In the early 1650s he served as Cromwell’s deputy in the successful campaign against the Scots, and was later to rise to both high military and state office.

Lambert may well have learnt his love of gardening, along with his grounding in military affairs, from Lord Fairfax, the Parliamentary general whose house and garden at Nun Appleton was famously described in verse by Andrew Marvell.

Wimbledon Palace, by Henry Winstanley, 1678

https://www.liveauctioneers.com/item/6514726

Lambert bought Wimbledon House, the former home of Charles I’s wife, Henrietta Maria, in 1652 for £16,822. The former queen had a fine garden created in the contemporary French style, and Lambert devoted himself to enhancing this, and to collecting art. He was said to grow “the finest tulips and gilly-flowers that could be had for love or money”.

Another royalist friend and fellow horticulturalist, was Sir Thomas Hanmer (1612-78), who gave him tulip bulbs including “a very great mother-root of Agate Hanmer” which he had raised himself. This was described by John Rea in Flora as “a beautiful flower, of three good colours, pale gredeline [ pinky grey], deep scarlet, and pure white, commonly well parted, striped, agoted [ with a marbled pattern resembling agate or chalcedony] and excellently placed, abiding constant to the last, with the bottom and Tamis [stamens] blue.” Lambert also imported many other bulbs from Holland.

from The Belgick, or Netherlandish hesperides ?that is, the management, ordering, and use of the limon and orange trees, fitted to the nature and climate of the Netherlands /by S. Commelyn ; made English by G.V.N.

The Parliamentary Survey of the royal estates in 1649, inventoried over a thousand fruit trees in the gardens at Wimbledon, particularly noting the “three great and fayer” fig trees that covered a very “greate part of the walls of the south side of the manor-house” “by the spreading and dilating of themselves in a very large proporcion, but yet in a most decent manner”. Henrietta Maria’s famous orangery [on the right in the image above] contained 42 orange trees planted in boxes, valued at £10 each, and 18 young ones, a lemon tree “bearing greate and very large lemmons” (£20) a “pomecitron” tree” (valued at £10), and six pomegranate bushes.

The vineyard was described as “well ordered and planted bearing very sweet grapes”. When Hanmer, who was a wine enthusiast as well as a lover of tulips, wrote some notes about vines years later, he referred to “the red Wimbledon grape” which “bears very thicke and is very good but not ripe till the end of September”.

Lambert’s gardening interests became so well known for them that political opponents satirized him, along with other Parliamentarians, in a pack of cards as “the Knight of the Golden Tulip”.

So here in the 1650s we have one of Cromwell’s most senior and trusted supporters asking a high-ranking political opponent who is living, supposedly incognito, in a foreign country – not about high politics but to ask him to get some rare tulip and anemone bulbs.

It may not quite be the equivalent of Obama exchanging friendly messages on Facebook with Vladimir Putin ….. but it does show that horticulture and love of gardening cut across most conventional boundaries.

An additional factor may be that Lord Hutton was tired of exile in poverty – he had amassed massive debts of £45,000 during

Hatton House [the former Ely Palace, now the site of Hatton Gardens and Ely Place, from Faithorne and Newcourt’s Exact Delineation published 1658

Meanwhile Lambert fell out with Cromwell and in 1657 retired to Wimbledon where he was accused by Lucy Hutchinson, the Puritan diarist, of plotting vengeance and “dressing his flowers in his garden and working at the needle with his wife and his maids”. [ Memoirs of the Life of Colonel Hutchinson, ed N. Keble, Phoenix Press, 2000, p257]

He probably would have stayed there had it not been for the changing political situation following Cromwell’s death in 1658. He moved to support Richard Cromwell’s succession as Protector and took charge of the army. When Charles II returned the parliamentary forces melted away, and Lambert was arrested and eventually put on trial. At the age of 41 he was condemned to be executed but his sentence was commuted to life imprisonment by the king and he was sent to Castle Cornet on Guernsey, where the Governor was to “give such liberty and indulgence to Colonel John Lambert within the precincts of the island as will consist with the security of his person”. The Governor was none other than Lord Hatton.

Castle Cornet before 1672 when an explosion destroyed the keep, by Isaac Sailmaker

http://museums.gov.gg/castlehistory

A model of Castle Cornet from

http://www.northlincsweb.net/Lambert/html/castle_cornet.html

It was not a totally happy encounter. They may have been united by their love of flowers – Lambert was allowed to devote his time at the castle to horticultural interests, and created a garden on the top level next to the round tower, between the 2 parallel walls – but they were about to be divided by love.

Lambert’s family, including his daughter Mary, were allowed regular visits and even stayed on the island. Hatton’s entire family, including both his sons, was also resident. The inevitable fairy-tale encounter took place. Charles Hatton fell for Mary Lambert and they married but it was a clandestine affair.

Lord Hatton apparently did not find out for more than a year and when he did he was furious, as was Charles II, who thought the liaison with such a prominent ‘traitor’ was because of laxness and complicity on Hatton’s part. Hatton responded by telling the king that the match was made entirely without his knowledge, and how strongly he disapproved. So strongly in fact that he turned his son out of doors, and cut him off without a penny. Nevertheless Charles II removed Hatton from his governorship, and Lambert was later moved to Drakes Island in Plymouth Sound where he eventually died in 1684. [For more about Lambert, see David Farr, John Lambert: Parliamentary Soldier and Cromwellian Major-General, 1619-1684, Boydell, 2003]

It all goes to show that gardening does cut across all sorts of boundaries BUT there are still limits. It’s fine to buy tulips and anemones for your political enemies … but you certainly don’t want your children to marry them!

![Two broken tulips, beetle, and a snail Nicolas Robert, 1614-1685] Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge](https://thegardenstrustblog.files.wordpress.com/2015/06/fwc_pd-109-1973-24_.jpg?w=275&h=397)

Pingback: Creating Kirby | The Gardens Trust