Caroline of Ansbach (1683–1737), as Princess of Wales

by Godfrey Kneller(c) National Trust, Oxburgh Hall;

In the 1720s and 1730s the gardens at Richmond Lodge (now part of Kew Gardens)were the “special domain” and “spiritual oasis” of a remarkable and underestimated woman who created a carefully staged landscape that was renowned throughout the country and indeed abroad. Although much of her work was swept away by Capability Brown a few decades later her innovation in English garden making should not be overlooked. The woman was Caroline of Ansbach, wife of George II.

detail from “Revised design for Queen Caroline’s Hermitage in Richmond Gardens”, by William Kent

Sir John Soane’s Museum

Read on to find out more about one of the garden buildings that she had constructed in the royal gardens there: the Hermitage

The future George I with his son, the future George II and Caroline

http://www.hrp.org.uk/kensington-palace/history-and-stories/palace-people/queen-caroline/

Caroline was very well educated and deeply religious but not in a dogmatic way. She had been bought up a Lutheran in a very liberal and enlightened court and had already turned down an offer of marriage because it involved becoming a Roman Catholic when she was offered the hand of George, Prince of Wales in 1704.

She was a friend of Gottfried Leibnitz, the eminent scientist and philosopher, who was a member of her parent’s court, and, like him, she believed that science supported the existence of a divine creation and provided proof of religion. She welcomed, indeed promoted, religious debate and openness and, as a result, protected unorthodox thinkers and clergy, advancing their careers wherever she could.

Part of an engraving of George II & Caroline’s coronation procession, artist unknown, reproduced in Parliament Past and Present by A. Wright and P. Smith (London, 1902).

When the new Princess of Wales arrived from Germany in 1705, the Hanoverian Court was, to put it politely, not renowned for either its interest in culture or gardening. She must have been surprised by its insularity, and immediately began to involve herself in London’s scientific, religious and artistic life. She was such a generous a patron of the arts in all their forms, but especially horticulture, that when she died she was £20,000 in debt.

The gardens at Kensington Palace , drawn for

Britannia Illustrata (1707-8) and dedicated to “Her most Serene and most Sacred Majesty, Anne” showing the gardens as designed by Henry Wise & before Caroline began her alterations.

Caroline was a knowledgeable and enthusiastic gardener and employed both Charles Bridgeman and William Kent to devise improvements in Hyde Park, Kensington Palace, and St James’ Park as well as at Richmond Lodge. She turned Kensington into a lively centre of court life, despite the fact that George II was a bit of a bore, and more interested in campaigning than culture. She began a menagerie in the palace grounds, which included tigers while apparently the King remained content with snails and tortoises! She also allowed the palace gardens to be opened to the public when the Royal Family were at their country retreat at Richmond.

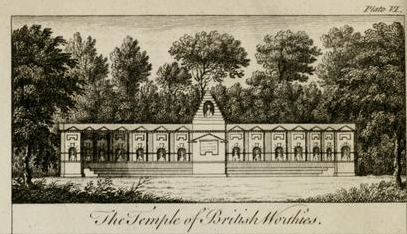

As queen she employed both Charles Bridgeman and William Kent to work on the gardens at Kensington and at Richmond. There were a whole range of new buildings put up, including, at Richmond, a pavilion, a dairy, a rotunda and a menagerie. These are marked on John Rocque’s Survey of 1754.

detail from The Mount and Revolving Summer-house by Bernard Lens, 1736 taken from Revolving Architecture By Chad Randl

At Kensington the most famous was the revolving summer-house on top of the mound created from the excavations for the Serprentine. In spite of her gardeners’ fame and experience there is no doubt is was the Queen in charge, with Bridgeman admitting that everything was done “as Her Majesty shall direct”.

At the same time Caroline took a serious interest in British politics and, once her husband had succeeded to the throne in 1727, she became the power behind the throne and held the ring between her husband, George II and Sir Robert Walpole, the already long serving leading Whig minister, whose ally she had long been. She was very conscious of the Germanness of her entire family and the new dynasty’s lack of an enthusiastic English following, and was determined to do whatever she could to alter the situation. As part of this she drew on the growing interest in British history and sought to turn it to dynastic and Whig advantage, by stressing the virtues of Englishness and in particular the anglicization of the royal family. Her support for the Whig cause is commemorated in a grand column erected in her honour at Stowe.

As I tried to show in recent posts about the Druids, there was a strong and growing interest in the past and in particular in creating a comprehensive ‘national history’. Of course, which events and aspects of the past were chosen depended on who was doing the writing and the interpreting! Both major political parties drew on the past to validate their actions, and our long running wars with France and the ever-present fear of royal absolutism that was embodied by Louis XIV added extra impetus. Much of the political debate revolved around the origins of English ‘liberty’: these were rediscovered or invented where necessary, and then merged with elements of anti-Catholicism and anti-Jacobite feeling (both still rampant political forces in Britain), as well as ever-present xenophobia. The result was a hybrid ‘national genius’ in which Druids, Arthurian legends, our Saxon ancestors, Norman, mediaeval and Elizabethan elements were all grist to the mill.

The most famous translation of this into the garden is, of course, at Stowe which is contemporary with Caroline’s designs at Richmond. The political overtones in both are obvious and similar. And there are similarities in style with buildings in the other great garden being created at the same time: Lord Burlington’s Chiswick.

This is not surprising. Burlington was a leading Whig until 1733 when he broke with the Queen’s friend Robert Walpole. Burlington would have known the Queen and her views very well – and vice versa – especially since his wife, the Countess, was one of Caroline’s Ladies in Waiting. They both clearly agreed there was a need for the rebirth of the arts in Britain, but Caroline went one stage further than the earl and was not just concerned with the aesthetic. It was her lifelong interest in theology and philosophy that meant she encouraged William Kent to use “a new precocious visual language that enlarges the meaning of the whole” when he designed The Hermitage. [Judith Colton, ‘Kent’s Hermitage for Queen Caroline’, Architectura, no.2 1974]

detail from Architectural drawing of the Temple, or Banqueting House, in the park at Euston Hall, Suffolk, ca. 1746, by William Kent (1685-1748), V&A

The Hermitage was a garden pantheon in honour of the rationality of science and religion. Started in November 1730 and costing £1,114 it was an early attempt by Kent to marry formal classicism with what was already being called ‘Saxon’ architecture. It was a rustic three-part Temple, with a prominent central pedimented bay and a miniature bell-topped tower. Inside was an octagonal room. In form it was similar to the Temple that Kent designed for Euston or the Queen’s Temple at Kensington.

But the finish was very different. Classical blockwork and arches were rusticated and distorted, the roof comprised of rough-hewn stone slabs and the whole building set into a mound and surmounted by trees.

The Gentleman’s Magazine described it as “a heap of stones, thrown into a very artful disorder, and curiously embellished with moss and shrubs, to represent rude nature. ”

A plan of the Hermitage from Some designs of Mr. Inigo Jones and Mr. Wm. Kent

by Jones, Inigo, 1573-1652; Kent, William, 1685-1748; Vardy, John, d. 1765

The writer then went on that he was ” strangely surpris’d to find the entrance of it barr’d with a range of costly gilt rails, which not only seemed to show an absurdity of taste, but created in me a melancholy reflection that luxury had found its way even into the Hermit’s Cell.”

This indigested pile appears The relict of a thousand years As if the rocks in savage dance Amphion hither bought by chance”

While the exterior was designed to give the impression it had been there since antiquity, the elegant classical interior would not have been in place in any aristocratic mansion.

The main room contained 5 busts of great theologians and scientists who were far from ‘safe’ in theological terms and who sent a very clear message about the “daring and speculative character of the Queen’s beliefs” (Peter Quennell, Caroline of England, 1939)

The first bust was of Samuel Clark (1675-1729) who she had met soon after her arrival here and whose correspondence with Leibnitz she encouraged and then later arranged to be published. Clark was a Cambridge divine and deist who believed that “that no article of Christian faith is opposed to right reason.” This led Bishop Gibson to remark to Queen Caroline that Clarke was “the most honest and learned man in her dominion but with one defect – he was not a Christian”. [cited by Basil Willey, The Eighteenth Century Background, 1940)

Her second choice was William Woolaston who was if anything even a more serious challenge to the conventional and High Anglican end of the church. “Potentially a Candide” his “The Religion of Nature”quoted more from classical sources such as Cicero, Seneca, Plato and Aristotle than St Paul or Moses.and caused great scandal.

The three remaining choices were all well known and respected English scientific and philosophical figures. Isaac Newton, John Locke and Robert Boyle. They represented “the glory of their country and stamped a dignity on human nature…… they paved the way for concepts of liberty and public happiness.” Robert Boyle was put at the centre of the group for his supposed centrality to thinking of the others.

“Nature, O Boyle tho’ hid in night Her laws, to thee were clear as light Such worth again where shall we meet Or where a queen so good, so great?

The interior of the Hermitage from Some designs of Mr. Inigo Jones and Mr. Wm. Kent

by Jones, Inigo, 1573-1652; Kent, William, 1685-1748; Vardy, John, d. 1765

The careful use of sculpture at the Hermitage also allowed the Queen to be seen as a virtuous patroness or an “ancient in modern times.” Its rural setting was regarded as proper for the contemplation of religion, morality and even science.

Of course the Queen’s message was not always well received. One uncharitable critic remarking…..

“Three holes there are thro’ which you see, Three seats to set your a–e on , And idols four – of wizzards three, And one Unchristian parson”

There was another message too. As I said earlier Caroline was astute enough to realise that the royal family needed to assimilate, to become English rather than remain German. She knew it would be political folly to do otherwise. The Hermitage was to show her own attachment, and that of her family, to her new kingdom, its history and customs, and it succeeded. As the Gentleman’s Magazine records “her own Liebnitz” was left out to show her “loyalty to and National Pride in great Britain” and she “built herself a Temple in the hearts of the People of England who will by this instance of her love of liberty and publick virtue think their own interests as safe in the hands of the Government as in their own”

And of course a Hermitage had to have a hermit. This was Stephen Duck.

Duck came from a poor agricultural background and was largely self-taught. He became known as ‘the thresher poet’ after one of his early works, was then ‘discovered’ and eventually introduced to a lady in waiting of the queen, and then to Caroline herself in 1730. He quickly gained her favour but once he became the resident hermit he was not permitted to come to court “that Her majesty may be freed from any troublesome solicitations …(from) the epigrammatic Maecenas” .[from Lady Sundon’s letters] Duck later to marry Caroline’s housekeeper at Kew and was ordained.

If you want to know more about him or read any of his poetry then a couple of good places to start are firstly his collected poems, which come with a brief biography by Joseph Spence, and secondly in letters by Viscountess Sundon, Caroline’s Mistress of the Robes:

https://archive.org/stream/poemsonseveralo00spengoog#page/n167/mode/2up

https://archive.org/stream/memoirsofviscoun01thom#page/178/mode/2up/search/duck

Drawing of Queen Caroline’s Hermitage in Richmond Gardens

by Bernard Lens III (1682 – 1740) c.1735.

Royal Collection Trust

The Hermitage stood as a proof of Pope’s comment that “gardening is near akin to philosophy” ; a symbol of the contrast between absolutist Europe, the ‘dark continent’, and the ‘light of English liberty’ supported by an enlightened monarchy. But it was only one part of Caroline’s construction work at Richmond, and if you thought the Hermitage was a bit odd or over the top just wait until next week’s post!

Pingback: Ornamental Hermits … Time for a Comeback – The Silverback Digest

Pingback: Ornamental Hermits Were 18th-Century England’s Must-Have Garden Accessory – CavemanGardens

For more information on this subject please take a look at my blog

https://bathartandarchitecture.blogspot.co.uk/2015/08/queen-carolines-hermitage-at-richmond.html

and for Queen Caroline’s portrait busts see –

https://bathartandarchitecture.blogspot.co.uk/2017/10/marble-bust-of-queen-caroline-by.html