A Building for the Termination of a Walk in the Chinese Taste, from Rural Architecture in the Chinese Taste.

It was hard not to smile when, whilst researching for a lecture on Chinoiserie in the garden, I flicked through the pattern books published by William Halfpenny, a virtually unknown 18thc architect.

Very little of his work appears to have survived, although what does is impressive and suggests that perhaps he has been under-rated. In particular the recent re-creation of the Chinese bridge that he designed for Lord Coventry at Croome Park is an elegant reminder of his ability.

But really his fame, such as it is, now mainly rests on a series of books of architectural designs for garden structures and other features, which are often whimsical when they are not pure comic fantasy. Halfpenny clearly had a vivid imagination so read on to find out more and, I hope, be at least mildly amused…

Plan and Elevation of a Temple or Summer House on a Tarrass in the Chinese Taste, from Rural Architecture in the Chinese Taste

Little is know about Halfpenny’s early life although he was probably a Yorkshireman. By 1725 he was living at Richmond in Surrey where he worked as a carpenter. At the same time he had also begun writing a series of quasi-mathematical books aimed at helping ordinary builders do things like calculate the proportions of architectural orders, and draw arches and other features in perspective. Practical Architecture was published in 1724, followed in 1725 by The Art of Sound Building, and then in 1728 by The Builder’s Pocket-Companion and Magnum in parvo (1728), and finally Perspective Made Easy in 1731.

Around this time he seems to have moved to Bristol, and from there over to Ireland to try his hand as an architect. That didn’t work, so after a spell back in Bristol eventually he returned to London in the late 1740s and back to writing builders manuals. Arithmetic and Measurement, his first new book for seventeen years was published in 1748 and was followed by Andrea Palladio’s First Book of Architecture (1751)—in which he claims to point out and then correct the mistakes in the perspective in some of Palladio’s plates. Geometry, Theoretical and Practical followed in 1752.

from Rural Architecture in the Chinese Taste

If this had been all he wrote then Halfpenny would probably have been totally forgotten. Luckily it wasn’t, and the last few years of his life were filled with a stream of inexpensive architectural design books that covered everything from farmhouses to garden grottoes, in every conceivable style from the rustic primitive to Chinese fanciful via Gothic extravaganza. They were aimed at jobbing builders and ‘workmen at a distance from the Metropolis’ to give them ideas for ‘all manner of rural buildings in a wide variety of materials and in all the latest fashions at little cost’.

from A New and Compleat System of Architecture,

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.32044033499369;view=2up;seq=1

He began, in 1749, with The New and Compleat System of Architecture which contained designs for what Eileen Harris the architectural historian described as “more ambitious houses in a ‘decorated’ Vanbrughian or bastardized Palladian style”. Its principal interest to garden historians is the collection of rather elaborate garden gateways that he includes.

from A New and Compleat System of Architecture,

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.32044033499369;view=2up;seq=1

But then, somehow, Halfpenny managed to catch the zeitgeist of the mid-18thc.

The Elevation of a temple partly in the Chinese Taste, from ‘New Designs for Chinese Temples’, published 1750-52 (engraving)

China was becoming a great source of inspiration in every field of design – wallpaper, furnishings, ceramics and although Halfpenny almost certainly knew nothing about China he was adept enough to switch from classically inspired designs to others based loosely on “the oriental”. His pattern books for chinoiserie offered ideas for extending the style beyond temples, to bridges, garden buildings and even garden furniture.

From Rural Architecture in the Chinese Taste https://archive.org/stream/ruralarchitectur00half_0#page/n3/mode/2up

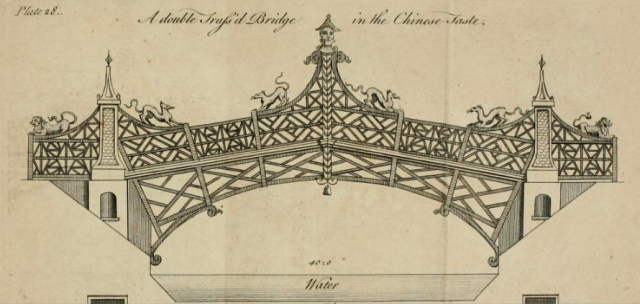

Working with his son, John, he published New Designs for Chinese Temples, which came out in four parts between 1750 and 1752.

The first part contained relatively simple structures, and in it Halfpenny gives brief details of the sizing, materials and even possible costs. The seat on the right for example is “supposed to be fixed at the Termination of a large Walk, and its Width in the Clear is 17 feet, and 14 feet high from the Floor to the Foot of the lower Cove, and 22 feet in Front; the back Wall up to the Pitch may be built of Brick, or Timber filled with 4 Inch Brick; and the Ornaments may be made of Wood, decorated in the Chinese Manner, with netted work etc. Which may be executed for about £100.”

From Rural Architecture in the Chinese Taste https://archive.org/stream/ruralarchitectur00half_0#page/n3/mode/2up

A Termany Seat in the Chinese Taste, From Rural Architecture in the Chinese Taste https://archive.org/stream/ruralarchitectur00half_0#page/n3/mode/2up

Part one was “so well received” that Halfpenny was encouraged “to add many improvements thereto…” Parts 2, 3 and 4 followed over the next year or so with more complex buildings and structures, as well as designs for interior fixtures and fittings.

From Rural Architecture in the Chinese Taste https://archive.org/stream/ruralarchitectur00half_0#page/n3/mode/2up

This is, somewhat surprisingly, a significant book in the history of design because it predates the much better known works of Sir William Chambers and the furniture designer Thomas Chippendale, who are usually thought of as the people who ‘introduced’ the fashion for chinoiserie to Britain.

From Rural Architecture in the Chinese Taste https://archive.org/stream/ruralarchitectur00half_0#page/n3/mode/2up

It is also includes, according to the Oxford English Dictionary the first recorded use of the word gazebo in English.

From Rural Architecture in the Chinese Taste https://archive.org/stream/ruralarchitectur00half_0#page/n3/mode/2up

The four parts were then reissued, almost immediately, as one single volume: Rural Architecture in the Chinese Taste in 1752. It carried a short preface in which Halfpenny wrote “the Chinese Manner of Building being introduced here with Success, the few following Essays are an Attempt to rescue those agreeable Decorations from the many bad Consequences usually attaching such slight Structures, when unskilfully directed: Which must often unavoidably happen at a Distance from this Metropolis, without such Helps as, I flatter myself, the Workmen will here find laid down by Their Well Wisher, William Halfpenny.”

From Rural Architecture in the Chinese Taste https://archive.org/stream/ruralarchitectur00half_0#page/n3/mode/2up

The books clearly had a wide appeal, and showed the aspirations of the commercial and professional middle classes. One of Halfpenny’s plates was reprinted in The Connoisseur Magazine in 1756 alongside a satirical poem which read:

From Rural Architecture in the Chinese Taste https://archive.org/stream/ruralarchitectur00half_0#page/n3/mode/2up

“The Cit’s Country Box”

The traveller with amazement sees

A Temple Gothic or Chinese

With many Bell and tawdry rag on,

And crested with the sprawling dragon

A wooden arch is bent to stride

A ditch of water 4 feet wide

With angles, curves, and zigzag lines,

from Halfpenny’s exact designs.

From Rural Architecture in the Chinese Taste

from Rural Architecture in the Gothick Taste https://archive.org/stream/ruralarchitectur00half#page/n0/mode/2up

Halfpenny obviously decided to cash in the success of his Chinese designs. Next came Architecture in the Gothick Taste,”being twenty new designs, for temples, garden-seats, summer-houses, lodges, terminies, piers, &c. : on sixteen copper plates : with instructions to workmen, and hints where with most advantage to be erected.”

from Rural Architecture in the Gothick Taste

Few of the designs bear more than a passing relation to Gothic and Halfpenny seems happy to be as eclectic and imaginative as he felt like!

from Rural Architecture in the Gothick Taste

from Rural Architecture in the Gothick Taste

At the same time Halfpenny continued publishing more traditional pattern books and builders books including Twelve Beautiful Designs for Farm-Houses (1750, 1759, 1774), and Useful Architecture (1752, 1755, 1760), but The Country Gentleman’s Pocket Companion (1753, 1756) is where his eclecticism really shows. It has designs of all kinds, often recycled, and mixed up.

from The country gentleman’s pocket companion

from The country gentleman’s pocket companion

from The country gentleman’s pocket companion

from The country gentleman’s pocket companion

from The country gentleman’s pocket companion

from The country gentleman’s pocket companion

The orangery at Frampton Court, http://www.framptoncourtestate.co.uk/orangery.htm

Did anyone actually use his books for a design source? Apparently so, according to several architectural historians, and there were even some examples taken from his books that were built in the American colonies, although I can’t find any visual evidence of that.

A few of Halfpenny’s own buildings do survive, notably the former Coopers Hall built c1743–4, which is now the main entrance to Bristol Old Vic.

Coopers Hall, Bristol

Amongst other possible attributions are the delicate Orangery at Frampton Court, and the rather more solid and bizarre Black Castle, which is built from industrial waste, both near Bristol. I can find no trace of anything remotely oriental in any of the buildings possible attributions to him.

The Black Castle

http://brisray.com/bristol/bbris.htm

However there is one thing Halfpenny designed that does shows more than traces: the bridge across the artificial river at Croome Park, Worcestershire,which he illustrated in his last book, Improvements in Architecture and Carpentry, in 1754.

from ‘Improvements in Architecture and Carpentry’, 1754.

The Croome accounts show that Halfpenny was paid in 1750 and 1751, at the same time Capability Brown’s involvement began, which suggests that the bridge was finished by 1751. It can be seen on Doharty’s estate plan that year although the canal/river it bridges was then still incomplete.

Doharty’s estate plan of Croome, 1751.

Image from Jeremy Milln’s report on the bridge for the National Trust, May 2014

https://www.academia.edu/7092994/Chinese_Bridge_at_Croome

Croome Park, by Richard Wilson 1758, National Trust

It can also be seen, much more clearly, in the painting by Richard Wilson which records the landscape in 1758. It appears to have been deliberately taken down in the 1810s and replaced by a simpler structure.

A model of the replacement bridge

http://www.greenoakcarpentry.co.uk/news/croome-chinese-bridge/

All obvious traces had long disappeared when in 2009, and again in 2014, archaeology students from the University of Worcester set out to find it as part of National Trust’s landscape restoration project.

A recreation in green oak was opened in the summer of 2014. The full story of its loss, rediscovery and recreation can be found at the National Trust Treasure House blog:

https://nttreasurehunt.wordpress.com/2015/08/11/the-chinese-bridge-at-croome-rebuilt/

Sadly although his Chinese and Gothic flights of fancy earned Halfpenny a name in architectural history, and probably make us smile, they were not enough to make his fortune and he died in debt in 1755.

You can easily read or download many of Halfpenny’s books on-line and a good place to start if you are interested in doing that is:

http://onlinebooks.library.upenn.edu/webbin/book/lookupname?key=Halfpenny%2C%20William%2C%20-1755

You must be logged in to post a comment.