I was recently sent a book about treehouses for my birthday and it was a subtle reminder that we’d inherited the remains of one here in France when we bought the house 15 years ago and even laid the boards for another in a willow tree over the lake. Alas the best laid plans of mice and garden owners gang aft a-gley as Robbie Burns didn’t quite say, and the treehouse’s base still sits unfinished. Having looked at the book though maybe one day !

I was pleased – as well as surprised – to see that one of the authors was Paula Henderson a historian I admire and whose work on early modern gardens has been groundbreaking. I had no idea she was interested in treehouses and wondered what the possible connection was between them and the Tudors. You don’t somehow imagine Henry VIII sitting in an oak tree or Elizabeth I clambering up a ladder for the view.

Of course I ought to have known but as I flicked through the section on treehouses of the past the penny quickly dropped….

Of course treehouses by their very nature are ephemeral and there are very few really old ones left anywhere. Almost certainly the oldest survival is the one at Pitchford Hall, a half timbered Elizabethan house, in Shropshire which was first mentioned in 1692. A makeover in 1760 gave it ogee windows and a moulded ceiling inside. At one point apparently it was covered in stonework-effect cladding to look like a little watchtower but modern restorations have removed this so it now matches the house. It sits in and on an ancient lime tree, although now both are supported by steel props.

But if there are few historic survivors there are descriptions and even the occasional image of others.

The earliest one I’ve seen mentioned is the one built for the emperor Caligula [12-41 AD] who called it “his nest”. According to Pliny’s Natural History :”That prince was so struck with admiration on seeing a plane tree in the territory of Veliternum, which presented floor after floor, like those of the several stories of a house, by means of broad benches loosely laid from branch to branch, that he held a banquet in it.” The dining space was “formed for the reception of fifteen guests and the necessary attendants.”

When the Renaissance rediscovered, translated and then printed classical writers like Pliny, making them available to a much wider audience, it may have inspired a revival of interest. Certainly there’s evidence of treehouses in print and paintings from the last few years of the 15thc.

The first image I’ve found is from the Netherlands where Hieronymous Bosch included an extraordinary treehouse in the background to his painting of St Christopher carrying the Christ child which dates to c 1490-1500. Heaven only knows why but given that Bosch clearly had a vivid imagination and invented many weird and wonderful scenes perhaps this was just another of them? Bosch’s weird imagery with its morality tales and scenes of hell and purgatory was very popular – and they included all sorts of versions of houses and other structures in trees, on stilts and on grotesque creatures.

One person Bosch certainly inspired was Pieter Breughel the elder, well known as a painter of peasant life but who also worked as an engraver. In some of his prints there are more fantastic treehouse-like creations, in the style of Bosch.

But the Netherlands wasn’t the only place where tree houses, albeit bizarre ones, seem popular this early. At around the same time, 1496-98, Leonardo da Vinci was decorating a room in the Castello Sforzesco in Milan with trompe l’oeil tree trunks rise up the walls and then extend their branches to cover the entire ceiling, with a dense and complex interwoven pattern of branches and foliage. The Sala delle Asse is like a faux treehouse inside an actual tower.

Then in 1499 Francisco Colonna published his almost unpronounceable Hypnerotomachia Poliphili or The Dream of Poliphilus which tells the story of Poliphilo pursuing his love, Polia, through a dreamlike landscape. Sadly, although the book has many woodcuts there isn’t one of the treehouse which Colonna describes as “altogether of Cytrons, Orenges and Lymonds, bushing with their leaves one within an other, and artifitially knitte and twisted togither, and the thicknes mee thought of sixe foote: with a Gate in the middest of the same Trees, so wel composed as is either possible to bee thought or done. And above in convenient places were made windowes, by meanes whereof, the bowghes in those places were to be seene bare, but for their greene leaves which yeelded a most sweet and pleasant verdure…And afterwardes I might perceiue, that in the interstitious thicknes, the bowghes (not without a wonderful woorke) were so artificially twisted and growne togither, that you might assend vp by them, and not bee seene in them, nor yet the way where you went up.” [from 1592 English tranalstion]

Despite its name Colonna’s book was widely read and seems to have influenced garden makers from the Medici rulers of Florence onwards. There is evidence of treehouses in the gardens of several of their villas.

There was one at Castello, the country residence of Cosimo de Medici, the first Grand Duke of Tuscany, just two miles from the centre of Florence. It may have disappeared by the time that Utens painted the villa and its garden, or it may have stood outside the paintings limits. However there are at least 3 descriptions – but sadly no images. They are too long to quote in full in here, but I’ve put in links if you are interested.

Giorgio Vasari in his Lives of the Artists first published in 1550, included the life of Nicolo il Tribolo who designed the garden’s various water features. Vasari records that Tribolo had “arranged an oak in a most ingenious manner… it is so thickly covered both above and all around with ivy intertwined among the branches, that it has the appearance of a very dense grove, one can climb up it by a convenient staircase of wood similarly covered with ivy, at the top of which, in the middle of the oak, there is a square chamber surrounded by seats, the backs of which are all of living verdure, and in the centre is a little table of marble with a vase of variegated marble in the middle, from which, through a pipe, there flows and spurts into the air a strong jet of water, which, after falling, runs away through another pipe. These pipes mount upwards from the foot of the oak so well hidden by the ivy, that nothing is seen of them, and the water can be turned on or off at pleasure by means of certain keys; nor is it possible to describe in full in how many ways that water of the oak can be turned on, in order to drench anyone at pleasure with various instruments of copper, not to mention that with the same instruments one can cause the water to produce various sounds and whistlings.”

There are other descriptions by French writer and philosopher Michel de Montaigne who visited Castello in 1580 when the treehouse was clearly still in use. Montaigne dismissed the house as “of no great merit” but went on at length about the gardens, and especially its grand water engineering schemes. He said that on reaching the platform the foliage was so thickly entwined “there is no prospect to be got therefrom, save through certain apertures which it has been necessary to make here and there, by clearing away the branches.”

A few years later in 1594 the English traveller Fynes Moryson also described the treehouse, adding that in the chamber there was “a Fountaine, or a statua of a woman, made of mixt mettall (richer then brasse, called vulgarly di Bronzo,) and this statua shed water from all the haires of the head and there be seates which cast out water when they are sat upon.”

All in all the Castello treehouse must have been great fun… if that is you like being soaked!

At Pratolino, another Medici villa built for Cosimo’s son Francesco, the gardens were filled with all sorts of technical marvels including another fountain in an oak tree: La Fontana della Rovere. The staircase up to it was captured in 1599 by Utens in one of his famous semi-circular paintings of the Medici gardens, although there’s no real sign of the platform.

However it can also be seen in a mid-17thc engraving by Stefano della Bella. The platform was about 8 metres across and as well as seats had a table that somehow had a waterspout that, like Castello, acted as a fountain. Sadly a storm later in the 17thc damaged the oak and both it and its treehouse had to be taken down.Nor was it just the Medici in sunny Florence who indulged in such tricks. Fynes Moryson had already seen one in Switzerland on his way to Italy in 1592. At Schaffhausen there was “a Lynden or Teyle tree, giving so large a shade, as upon the top it hath a kinde of chamber, boarded on the floors, with windowes on the sides, and a cocke, which being turned, water fals into a vessel through divers pipes, by which it is conveyed thither for washing of glasses and other uses: and heere the Citizens use to drinke and feast together, there being sixe tables for that purpose.”

detail from above

Some of these Medici villas contained another sort of treehouse, and one which was probably much more widespread because it did not require complicated hydraulic engineering to be successful, just complicated tree pruning and training skills.

Utens shows one in his painting of Pratolino at the other end of the garden to the oak tree fountain, and there’s another in his view of the Castello di Caffagiola.

These show a platform held up by ring of supporting poles round a central tree whose branches were trained and clipped to form a screen or wall around it, and a dome over it.

It was this style that spread rapidly across northern Europe perhaps because of the publication in 1582 of another difficult to pronounce book Hortorum viridariorumque elegantes by Hans Vredeman de Vries.

De Vries was a Dutch architect, engineer, artist and garden designer. Hortorum is the first book of garden designs, although none of them are real sites, or even thought to be related to real sites, and there is no explanatory text. Instead the whole series is presented in a uniform style to draw parallels between architecture and gardens, and to show de Vries expertise in using perspective.

De Vries shows how trees can be used to effectively create living buildings, with tunnels and bowers, and occasional raised paltform or treehouses at corners and intersections. Such living tunnels are the garden equivalent of the galleries seen in early modern palaces such as Henry VII’s Richmond or some of the buildings seen in the background of de Vries own prints in both Hortorum and his book of architectural designs.

As we saw in another earlier post such treehouses reached England too. Indeed John Parkinson notes in his section about Lime trees in Paradisi in 1629 that Lime “is planted both to make goodly Arbours, and Summer banquetting houses, either belowe vpon the ground, the boughes serving very handsomely to plash round about it, or up higher, for a second above it, and a third also : for the more it is depressed, the better it will grow.”

Unfortunately no images survive of the early example reported by Francis Thynne, one of the contributors to Holinshed’s Chronicles , the great Elizabethan history book. He noted that in 1559 “a banquetting house [was] made for her Majesty in Cobham Park, with a goodly gallery thereunto, composed all of green, with several devices of knotted flowers, supported on each side with a fair row of hawthorn trees, which nature seemed to have planted there of purpose in summer time to welcome her Majesty … “the same was artificially made”

Unfortunately Thynne is no more specific than that but luckily it must have survived a long time because John Parkinson also visited Cobham Hall and saw “a tall or great bodied Line tree, bare without boughes for eight foote high, and then the branches were spread round about so orderly, as if it were done by art, and brought to compasse that middle Arbour: And from those boughes the body was bare againe for eight or nine foote (wherein might bee placed halfe an hundred men at the least, as there might be likewise in that underneath this) & then another rowe of branches to encompass a third Arbour, with stayres made for the purpose to this and that underneath it : vpon the boughes were laid boards to tread vpon, which was the goodliest spectacle mine eyes ever beheld for one tree to carry.”

A slightly later example appears in the background of a portrait of James I’s young daughter Elizabeth, who was later the Winter Queen of Bohemia. Probably set in the grounds of Combe Abbey in Warwickshire, it shows a ring of trees trained to support a railed platform under a dome made of branches. Underneath is what seems to be a turf seat edged with wattle.

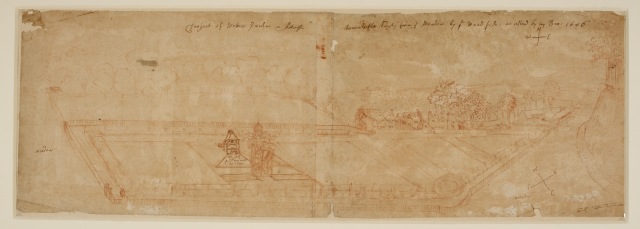

Dothill – image from Paula Henderson’s Treehouses.

Paula Henderson introduced me to another site I didn’t know about – Dothill Park in Shropshire where a 1626 estate map shows a pair of summerhouses on two branches of an ancient tree, one reached by a staircase, the other by ladder. It looks as if it could have stepped out of a drawing by Breughel or Bol.

Another 17thc example can be seen in a sketch by John Evelyn of the grounds of his brother’s house at Wooton in Surrey. On his return from an early trip to Europe in 1643 – a test exile – he had got permission to build a study in the garden, along with a fishpond, island and “other solitudes and retirements”.

Next to the study/summerhouse is a carefully detailed treehouse with ladder, platform and leafy roof which he himself may have designed or had built.

However Evelyn’s little platform was nothing compared to the famous Hollow Elm Tree of Hampstead. A 1653 broadsheet complete with an engraving by Wenceslaus Hollar shows a door at the foot of the tree, with stairs leading up through the hollow to a viewing platform at the top.

This was clearly a popular place for Londoners to visit and whoever owned it was clearly plagued with the kind of visitors all tourist attractions must dread. To read the various comments and verses which are too long to include here check this transcription.

Perhaps dating from the same time as Pitchford is the treehouse at Pishiobury in Hertfordshire. Captured in one of a series of beautifully naive engravings by Drapentier for Henry Chauncy’s The Historical Antiquities of Hertfordshire. which was published in 1700 after some 20 years of research. It shows an old fashioned house and surroundings with a range of country pursuits taking place, and there near the front is a rather splendid little treehouse.

But as the landscape garden began to take hold in England in the mid-18thc the idea of a treehouse must have seemed a bit old-fashioned, and there doesn’t seem to be much evidence of new ones being built. Even architects who specialised in the rustic like the Halfpennys and Thomas Wright don’t have examples of treehouses in their pattern books alongside the grottos and hermitages. Its not until the early 19thc that suddenly there’s a revival of interest as I’ll explain in next week’s post.

from the ceiling of the Sala della Asse

You must be logged in to post a comment.