Marion Cran http://carlisleflowers.net/women-garden-writers-in-early-20th-century-winterthur-museum-and-garden-delaware/

I often start these posts with a comments such as ‘here’s someone else you won’t have heard of”, although there’s often a good reason for the subject’s lack of fame … but today’s subject is someone who really has been unjustly neglected.

Marion Cran was the first woman gardening broadcaster as well as a highly successful and popular garden writer. You can judge how well she was renowned at the time by her inclusion, along with the still ‘famous’ Beverley Nicholls, in a comic rhyme by Reginald Arkell in 1934.

Beverley Nicholls and Marion Cran

Hadn’t been born when the world began

That is the reason I must confess

Why the Garden of Eden was not a success

Marion travelled widely writing about gardens abroad as well as Britain in 15 gardening books, and also produced a couple of novels, and assorted other books.

Marion travelled widely writing about gardens abroad as well as Britain in 15 gardening books, and also produced a couple of novels, and assorted other books.

She created two interesting gardens, one of which is still basically intact and being restored in keeping with her ‘spirit’. Yet her success there wasn’t matched by a similar success elsewhere. She often had financial problems and her private life was something of a mess with 3 husbands and a child out of wedlock – hardly a proper state of affairs for a respectable vicar’s daughter in the early 20thc.

Coggers at Benenden, photo by Louise and Colin, 2014, https://www.flickr.com/photos/c-l-english/17164777389

from frontispiece of A Woman in Canada, 1908

Edith Marion Dudley was born in South Africa in 1875 where her father Henry was a missionary. The family returned to England at the end of his term and she went to a girls boarding school in Brighton, and it may have been here that her interest in horticulture began as some of the girls had garden plots in the school grounds.

Marion was apparently married at a very early age although after the birth of her daughter Maidie, soon divorced, and the baby handed over to her ex-husband’s parents. She then trained as a nurse but a second daughter, Lesley, was born in 1902 after an affair with a married man. Meanwhile she started contributing articles to a range of magazines, before finding work at The Connoisseur, and then in 1903 as the first assistant editor at The Burlington Magazine. During this turbulent time she met George Cran, a London solicitor, who was older but comfortably off, and they married in 1905. She referred to George as King Cophetua, the king who fell in love with a beggar-maid and was immortalised by Burne-Jones.

Steephill Cottage, The Bourne, Farnham

Marion with her younger daughter Lesley and their dog Bouncer in the garden at Steephill. Photo courtesy of Dudley Graeme

George and Marion rented a flat in Sloane Square and looked for a weekend retreat in the country. This was to be “Steephill Cottage,” at the Bourne, at the time a semi-rural hamlet on the outskirts of Farnham in Surrey, classic commuter country even then, at only about an hour to Waterloo by train. The house stood in 3 acres mainly of pine woods but with several garden areas and Marion started to create a cottage garden, as well as having a kitchen garden, an aviary, beehives and goats.

Clippie, one of the Crans’ gardeners at Steephill. Photo courtesy of Dudley Graeme

It helped of course that she had two jobbing gardeners working for her. Farnham was also home to the rural writer and craftsman, George Sturt and not far from Munstead Wood, the home of Gertrude Jekyll. Marion met them both. This may have encouraged her to write up her experiences at Steephill which she referred to as her Garden of Ignorance and which became the title of her book with the subtitle: The Experiences of a Woman in a Garden.

The Rude Boy sculpture in the garden at Steephill, c.1913 Photo courtesy of Dudley Graeme

It combines prescriptive gardening advice with autobiography. She admits that, although she had longed to live in the country, ‘I knew nothing at all of gardening; never did anyone know less.’ When she first arrived at the ‘rented three shaggy acres of ground in Surrey’, it took her some time to decide to tame the wilderness. In an entertaining narrative, she describes her journey from ignorance of plants themselves, soil types and manures, planting aspects and pruning regimes, to hands-on expertise and wild enthusiasm. The Garden of Ignorance launched her horticultural career and she was elected a Fellow of the Royal Horticultural Society in 1913, a rare honour for a woman garden writer. So perhaps it is a sign of the book’s continuing appeal that it was republished by CUP in January 2017.

from the Marion Cran Album Collection. Courtesy of R.H.S. Lindley Library, London.

Unfortunately success in publication was not matched by success in her private life. George met someone else: “one less belligerent, an alien beggar maid much younger and nicer-looking than this old wife” as Marion put it. After their divorce in 1919 she could no longer afford the rent at Steephill, and had to find somewhere else to live. Luckily some mutual friends were also househunting and they told her about Coggers, an abandoned house they had seen near Benenden in Kent. Their description made her interested and Marion fell for the 14thc house as soon as she saw it, despite the terrible state it was in. She described later how the house had been used as a cowshed, had resident swallows, bats and squirrels, crumbling plaster, and trees growing through the floor boards of the main living room.

Marion outside Coggers. Photo from her album now in the Lindley Library

From The Garden of Experience, 1922

Her second horticultural book The Garden of Experience (1921), made her a household name in England and earned her enough money to be able to restore Coggers properly. It became her refuge from the world and a base from which to travel and write. Indeed the restoration was the subject of her next book The Story of My Ruin (1924), which was about the end of her marriage and the restoration of the house.

From The Garden of Experience, 1922

From The Garden of Experience, 1922

While she was working on Coggers she was offered the chance to do some radio talks about gardening on 2LO, which predated the foundation of the BBC. When the first of her Gardening Chats was broadcast on 6th August 1923 for a fee of 5 guineas, it made her the first gardening broadcaster.

She also contributed to the newfangled Woman’s Hour but these early years in radio were very much an experiment, with no fixed schedule or presenters. As things settled down lots of other people, including Vita Sackville-West, were trialled for the gardening slot, but in the end it was “the mellifluous Mr Middleton” who finally became the voice of horticulture on the radio.

Nevertheless Marion Cran had popular appeal because she never patronized her audience, but always tried to speak as “a learner talking to fellow-learners”, and she continued to make the occasional broadcast. These early broadcasts were subsequently published as Garden Talks (1925) and along with contribution from other garden writers and broadcasters including Vita Sackville-West, Beverley Nichols and Compton Mackenzie another collection of these was edited by Nicholls as How Does Your Garden Grow? in 1935.

Nevertheless Marion Cran had popular appeal because she never patronized her audience, but always tried to speak as “a learner talking to fellow-learners”, and she continued to make the occasional broadcast. These early broadcasts were subsequently published as Garden Talks (1925) and along with contribution from other garden writers and broadcasters including Vita Sackville-West, Beverley Nichols and Compton Mackenzie another collection of these was edited by Nicholls as How Does Your Garden Grow? in 1935.

The start of an article from Britannia & Eve, Oct 26 1928

Britannia & Eve 9 Nov 1928

In 1925 Cran also became garden editor for The Queen magazine, where she remained until 1930 but she was also contributing to a whole range of other magazines including Harper’s Bazaar, Good Housekeeping, House and Garden, Homes and Gardens, Britannia & Eve and Women’s Magazine, as well as newspapers such as The Bystander, The Daily Telegraph, Daily Mail, The Star, and The Standard.

Iris Mrs Marion Cran from the Historic Iris Preservation Society

http://www.historiciris.org/listings/mrs-marion-cran/

As a result of this national fame Marion found herself in great demand as a speaker, fete opener, and show judge, despite her constant assertion that she was no great horticultural expert, and it led to her becoming an early example of branding: everything from a “Marion Cran Bird Table” to Marion Cran calendars and garden dairies which continued until the mid-1930s. And of course several flowers were named for her, including at least 2 HT roses, an Iris, an orange-cupped Daffodil, a Crocus, a Gladiolus and a Delphinium. Sadly, as far as I can see, only the Iris introduced in 1923 by Amos Perry is still available.

Now she was on a roll. From then on much of her written output was shaped by her garden visiting both in Britain and around the world. A return visit to South Africa in 1926 led to The Gardens of Good Hope and was followed by The Joy of the Ground in 1929 about English gardens.

Now she was on a roll. From then on much of her written output was shaped by her garden visiting both in Britain and around the world. A return visit to South Africa in 1926 led to The Gardens of Good Hope and was followed by The Joy of the Ground in 1929 about English gardens.

In 1930, she switched to fiction with the rather racy [title at least!] The Lusty Pal. A second novel Piper’s Lay appeared in 1936 based on the life of her long-standing friend, the soldier and sculptor Fergus Scott Hurd-Wood who she married in 1933. According to her nephew Dudley Graeme, these two works of fiction earned her more than any of her garden books.

A book about her visit to the United States and Canada Gardens in America came out in 1931. Next she updated readers with a successor to The Story of My Ruin, about her more recent progress at Coggers with its flower gardens, orchard and ponds in Wind-Harps. I know a Garden in 1933 and Gardens of Character published just before the second world war described more English gardens.

But gardening books weren’t enough to live on comfortably enough for her taste, so at the same time she was, with Fergus, trying to set up a business breeding pigeons “The Premier Squab Farm” at Coggers which led of course to two more books The Squabbling Garden (1934) and Making the Dovecote Pay (1935). Sadly Fergus died soon afterwards and the business doesn’t seem to have been that successful since within weeks she was advertising the whole thing as “a going concern with orders in excess of supply” for £150pa or £1000 investment. [Times 17.2.1936] She was awarded a small Civil List pension in 1939 for services to Literature.

But gardening books weren’t enough to live on comfortably enough for her taste, so at the same time she was, with Fergus, trying to set up a business breeding pigeons “The Premier Squab Farm” at Coggers which led of course to two more books The Squabbling Garden (1934) and Making the Dovecote Pay (1935). Sadly Fergus died soon afterwards and the business doesn’t seem to have been that successful since within weeks she was advertising the whole thing as “a going concern with orders in excess of supply” for £150pa or £1000 investment. [Times 17.2.1936] She was awarded a small Civil List pension in 1939 for services to Literature.

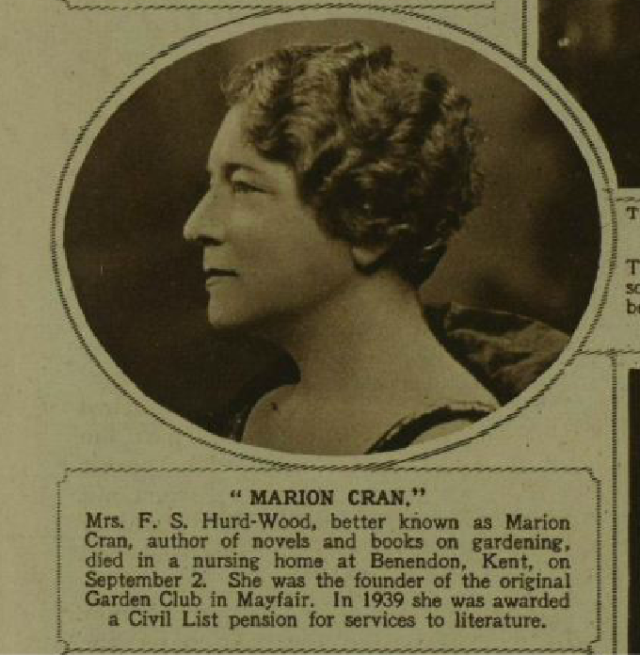

From Illustrated London News

The Times (London, England), Thursday, Sep 03, 1942

She suffered a heart attack in 1940 and could no longer live on her own. It did not help that her writing commissions began to dry up. She managed one last book Hagar’s Garden in 1941 which recorded her “exile from her beloved garden.” It was, said the Telegraph review, “surprisingly intimate” because it also was honest about her financial problems and her failing health. Staying with friends and being away from Coggers took their toll, and, although she did finally return to Coggers for a short while she had another heart attack and died in 1942. She is buried next to Fergus in the graveyard of the church in Benenden.

from Sevenoaks Chronicle 15th January 1943

Coggers was auctioned the following January and made £2900.

Cran’s reputation remained high and two anthologies of her writing were published in the years following her death. Leonard Grimble edited Garden Wisdom from the Writings of Marion Cran (1948) and Bedside Marion Cran (1951) noting in his introduction that “to read her pages is to enter a garden with her and to discover her as a genial companion whose mood is infectious” (1948, 19). That is still the case and if you don’t know her work I recommend that you take a look….

The Lindley Library hold several of her photo albums but I was surprised to find that there is no entry for Marion Cran in the ODNB, although there is an excellent PhD thesis by Cynthia Boyd about her work which is freely available online at: http://research.library.mun.ca/10190/1/Boyd_Cynthia.pdf

Pingback: Gardening for a Long and Happy Life - by Ethne Clarke

Thanks for the mention! I hope it helps a few more people to discover Marion and her works.

David